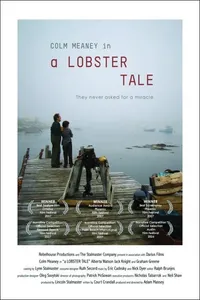

A Lobster Tale

The irony of Maine is that L.L.Bean gear engineered to make life bearable during days when 10 degrees is the high temp is too pricey for everyone who’s poor enough to have to live there year round. Rockefeller’s private carriage trails may be open to even the local masses now, but a cold war between the classes still exists between the locals, who suffer the extortion of winter with no respite, and the visitors from “away,” who can afford to enjoy the views, lots, cuisine and activities of vacationland summers.

At a back-of-the-case glance, it looked like “A Lobster Tale” could take on this paradox, the red-dyed-hot-dog highs and Allen’s-Coffee-Brandy-mixed-with-a-gallon-of-milk lows of Maine life. It’s the story of a good-hearted adolescent boy, his clam-shack-waitress mom and lowliest lobsterman dad (Colm Meany), who finds a clump of algae that can do miracles and is soon sought by all the townspeople for emergencies both real and, quite crudely for a kid’s movie, the impotence-variety. That hope was dashed at a minute-ten into the movie, at the shot of the lobster co-op … filled with half-round lobster traps. The kind that haven’t been used, outside of restaurant decoration, since the ’50s.

The movie sinks instantly into the water of Cliche Lake like a Ski-Doo into Chickawaukie Pond. Meany’s bait fish is glistening and firm, instead of disintegrating and maggoty, and he buys a single bucket of it: coupled with his casual clothing and pilothouse-less boat, that would realistically limit his fishing to about six days a year (that is, if the Coast Guard doesn’t drag him to court for guessing at the measurements of his lobster instead of using a $5 brass gauge). No wonder his wife is flirting with the bus boy and his son is the punching bag of the local rich boy: “I typed (my essay) on an IBM but it looks like you typed yours on an I-B-Poor!” Not that you stay sympathetic to the son, who gripes that he wants to run away “to Vermont, where no one even knows what a lobster is!” And having read somewhere that everyone in Maine says yes by saying “ayuh,” everyone in the movie says yes, every single time, by saying “ayuh.”

Magic algae aside, “A Lobster Tale” is about as genuine as the jerk-rockers of Blues Hammer in “Ghost World.” You’d do better to sit your kids in front of Sarah Palin’s acceptance speech, the part about the Alaskan pageant circuit and how, when she got knocked down by Miss Kodiak, her mama, the adorable little Catherine Eugenia Finnegan Palin, sent her back out and demanded that she bloody their noses so she could walk down that runway with pride. I’m sorry, I’ve misremembered Joe Biden’s speech. Regardless, “Roseanne” and “The Nanny” did a better job of exposing and rising above American class warfare, with more soothing voices.

The lives of the working poor in Downeast Maine would be a great backdrop for a movie, if you cared to get the details — and accents — right. Instead, “A Lobster Tale” dipped in for a taste of Maine like a Boston family in immaculate topsiders and shoulder-knotted sweaters for catered-on-the-beach lobsters dipped in gold instead of butter. No wonder its message is that only the few are worthy of decent lives and that those who strive to better their lot in life should swallow the scorn and derision of the haves like medicine.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.