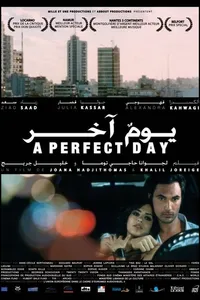

A Perfect Day

Hundreds of thousands died during the 15-year civil war in Lebanon that sets the stage for the kidnapping of the father figure in “A Perfect Day” (2005, not rated). The movie begins with a long shot of a young man’s head on a pillow, his overbearing mother worrying, “if he came back and said, ‘Why did you go?’ what would we say?”

Neither figure out how to answer that question as they begin the process of filing papers to have the father declared legally dead — and doing little the rest of the day.

The mother puts on some black clothing, ties her hair back in severe widow fashion, and scuffs downstairs in her house slippers to deliver Turkish coffee to three men who guard her apartment building. She makes ample allowances for frequent cell phone pestering of son Malek, who is suffering from insomnia. She stares, seeking divination, perhaps, into the grounds of her espresso cup. There is also the requisite scene of her petting her husband’s closet full of sport jackets.

Malek, meanwhile, ignores his mother’s calls, hands out cigarettes to old men and mostly pesters Zeina, an unappealing spoiled girl with a permanent Emma Watson look of scorn (it looks much better on Watson).

There are signs early on that something more important than Malek falling asleep in traffic will happen — he finds his father’s old, loaded, revolver. At a construction site, work halts because an old corpse is found. A beguiling doctor studying his sleep apnea shares a smoke break with him and murmurs, in ’70s adult movie style, that he’ll need to stay at the hospital another night for observation.

But outside of the energetic shots of pulsating Beirut, the movie lacks enough java juice to follow through on even its slightest teasing. The day ends with Malek pursuing Zeina into an irritatingly trendy club with dance platforms and sunken magenta settees. After sending him four inexplicably apologetic texts, Zeina ignores him until he passes out on said settee, then begins ferociously kissing him. They take to the streets, sucking face with eyes fully closed as cars shoot by, convinced perhaps that electromagnetism and Almaza beer will keep them from crashing into the other compact cars. Suddenly, Zeina takes out her contacts, has a temper tantrum and ditches the car, running into an alley into darkness. The movie ends soon after that, but not after the filmmakers decide a few minutes filming a moving version of meaningless coffee grounds — blurry city lights break from six dots into 15 and some shots of starlings wheeling as dawn breaks — will tell us what just happened.

We never find out if it’s something deeper than maternal nagging and paternal absence causing Malek’s insomnia. My theory? After the day’s shooting was done, he watched the dailies.