All Good Things

There’s often a case to be made with fictionalizing true history, or speculating using a framework of truth. Recently, there was a tantalizing article about one such project, in the works for years, in Slate. The still-untitled script by John Logan deals with a former cop turned private investigator and fixer for MGM in Hollywood in 1938, who cleans up the murder of a producer who’s married to a starlet and then goes on to solve the killing — with Judy Garland’s drug problems, an abortion by Lana Turner, and the sets of a Technicolor Munchkinland from “The Wizard of Oz” and a burning Atlanta from “Gone With the Wind” playing parts along the way. In 2008, Collider.com called the script “the worthy love child of ‘Chinatown.’” No freaking kidding. It’s hard to imagine a movie fan who wouldn’t be interested in seeing the finished product.

When it comes to the reality that inspires “All Good Things” (2010, rated R), though, one is hard-pressed to imagine why this actual case — and not just a fictional story about an heir who really did kill his wife and his friend and was caught only when he disposed of an accomplice — demanded to be turned into a movie. Was the rich man/poor girl story of Robert Durst and Kathleen McCormack particularly tragic? No. Did Durst’s alleged physical abuse of the accommodating McCormack, sparked after he relinquished his happy dream of a health food store in Vermont in order to slump back to the family millions in New York, speak to something iconic of the time or the institution of a damaged marriage? No. Or was it, as I suspect, the titillating bit we learn about in the end, which Dateline NBC led with in a 2008 story, calling Durst “a sometimes cross-dressing millionaire”? Really, in plot terms, the cross-dressing was nearly a throw-away detail, neither sexual nor compulsive, taken up without emotion, style or sexual motive when Durst escaped to Texas and only so he could stay under the radar.

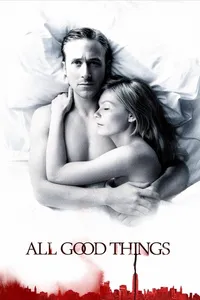

“All Good Things” does not transcend even that modest bar of real-life scandal, offering us a suitably creepy Ryan Gosling as the fake Durst, “David Marks,” but deflating all the anger and psychosis that simmer behind his clunky 80s serial-killer glasses and perfect white ski sweater by pairing him with a wife played by Kirsten Dunst, who in my mind hasn’t done anything memorable since 2000’s “Bring It On,” when she quite competently played a cheerleader. She was also decently cast as a ditzy female in 2004’s spectacular “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind,” though she had less range than Kate Winslet’s blue hair. In “All Good Things,” she is the glaring exception to everyone else disappearing into the early 80s. In hair, makeup, acting and dress, she evokes nothing more than Kirsten Dunst being a shat-upon girlfriend. It doesn’t help that she’s given the worst lines in the movie: “I’ve never been closer to anyone, and I don’t know you at all” and “I had an abortion. And… I don’t know what that is. If it’s something I did, or if it’s something I didn’t do” are two of the most eye-rolling examples. To make things worse, the movie — and its soundtrack, with its competing tracks of tense thriller strings and sad inside cry-music (and a continuity-shattering use of a track off the stellar 2003 album “Proyecto Akwid” in a later scene supposedly depicting 2000) can’t decide whether it wants to be a tale of doomed romance or one of financial intrigue in the dirty fringes of the last days of Times Square, where Durst’s/Marks’ family owned substantial real estate.

In reality, Durst — who is spending his days living in three homes in Texas, LA and New York on $65 million, the New York Times tells us — was merely questioned in the disappearance of his wife in 1982, and after the murder of a female friend of his who was believed to have knowledge of her death. When the disappearance case was re-opened, Durst went to Texas and killed an acquaintance — a jury decided it was in self-defense — then disposed of his body, for which he was convicted and served about a year. He’s never been charged in the other two killings. If there was any crime “All Good Things” convinced me he got away with red-handed, it was criminal drag dowdiness, even for Galveston, Texas. Apart from that, I just can’t get excited about this what-if murder mystery, or figure out what sort of crux “All Good Things” is supposed to revolve around. If the expository scenes of bliss in hippied-out Vermont were more than just New York counterpoint and early childhood reference, and contain the message one is meant to take out of this slow, eggshell-careful, tearstained, semi-bloody tale, it is merely this: if you have a messed up son who’s not interested in taking over the family business or having kids, spend some of your millions to get him the best damned analyst you can.

And if that doesn’t work, then let him keep his little granola store.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in the theater anymore. She lives in North Hollywood, near the In-N-Out Burger.