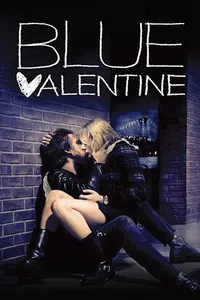

Blue Valentine

Here’s a romance that will punch you in the gut with insecurity, that will make you cry like you never cried as a teenager in love, a romance where everything happens like it does in real life.

Here’s a romance where there’s a beautiful girl, a noble boy who saves her and a little girl who loves them as fiercely as she loves the big, shaggy family dog. Know what happens to that beloved, home-videoed dog though? If you don’t watch the gate, it escapes and is run down by some careless driver on a weedy street. And the lovely girl and the handsome boy bury the beloved dog in secret, wrapping it in a tarp, rather than tell the painful truth.

“Blue Valentine,” Derek Cianfrance’s second movie, is about secrets. Not secrets hidden from one another, but secrets you don’t even admit to yourself, sprinkled across time like a disjointed dream, like a sleep-deprived memory on a tear-blurred highway escape. Secrets that can make your whole life’s work disappear like a wedding ring flung hard into a three-foot thicket of weeds.

Bruce Springsteen’s “Darkness on the Edge of Town” says everyone’s got them: “Some folks spend their whole lives trying to keep it. They carry it with them every step that they take, till some day they just cut it loose — cut it loose or let it drag them down, where no one asks any questions or looks too long in your face, in the darkness on the edge of town.”

The painful truth in this working class existence is that Dean (Ryan Gosling) signed on to Cindy’s (Michelle Williams) life when he was a scruffy furniture mover and she was a blonde medical student carrying another man’s three-month-old fetus.

He thought that would be the difficult decision. It wasn’t. The impossibilities lay far ahead — in Cindy, at the liquor store, running into the jock who came without a condom, pestering Dean for having a beer before he goes to work while she delays putting on her seatbelt in the family minivan, maybe secretly hating Dean for happily submitting to her flaws.

No one’s a hero here. No one’s the good guy. No one’s a victim. These are just young, small-town people in dim light, struggling, with no hope in sight.

Because they could have, would have, ditched each other long ago if she didn’t know how much he loved scooping up their little girl and eating raisins with her off the kitchen table, if he didn’t remember playing the ukelele as she tap-danced outside a closed bridal store to “You Always Hurt the One You Love.” For all the reasons she should love him, she kind of hates him. Deeper than that, she hates herself. She Can’t Do This Anymore, the cliche that explains nothing.

There are reasons (uncomfortable sex and unsexy drunkenness are two of them) why they don’t make a lot of movies about love in real life. The closest most filmmakers get is a glossed-over, self-congratulating, proudly haggard version of first world struggles, like in “The Kids Are All Right.” Or they go full-on parody like in “American Beauty,” which is dark, funny, incisive, bloody, full of rock and roll and money and bullets and makes you feel good about destroying the last 20 years of your life — as much of a fantasy as what the young, starry-eyed couple begin with.

At the end of “Blue Valentine,” as the audience watches blissful still frames destined for tragedy, they see a sign: “Is this you?” A filmmaker might as well show shots of car crashes: tiny shoes thrown from unsecured car seats, a woman’s purse emptied on a highway, a man’s glasses pulverized into a head-sized hole in a windshield. Is that you? We hope not. Can we fight against it? Sometimes, only in the tiniest sense. Sometimes, even with the things that are the most important to us, we can launch only the smallest fight. We know not where the assault is coming from. We might not want to know. These are the “lives on the line where dreams are lost and found.” Even if Dean had never showed up at Cindy’s door, offered to marry her, offered to be the father to her child, he, or what he symbolized, would still be there, just like Springsteen said, in the darkness on the edge of town.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in the theater anymore. She lives in North Hollywood, near the In-N-Out Burger.