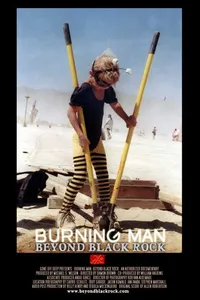

Burning Man: Beyond Black Rock

Well, that finally settles it. I’m never going to Burning Man.

It sounded pretty cool in college at the turn of the century. A weird-out-the-squares gathering in the middle of the Nevadan desert where you’d be surrounded by merry pranksters, weird art, fire, drugs and music — and no $8 beers and vinyl banner advertising. A Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade for the mushroom set. Homecoming for hippies. A pep rally on psilocybin.

But the way “Burning Man: Beyond Black Rock” tells it, people come to the week-long experience for new age platitudes that have nothing to do with exuberant counter-culture shrieking and freaking and everything to do with being a member of a certain set who has scads of time, money and mobility but very little self-awareness, who see the happening as something more noble than fun, about cutting-edge volunteerism and mind-blowing unity, passion without professionalism.

Sadly, that seems to be sort of the guiding concept of the filmmaking process in “Beyond Black Rock.” An early article on the film says it’s an hour, and one wishes that estimate had stuck. Instead, it’s 105 minutes but feels as long as the festival itself. The timeline is all over the place — one minute the party is underway and people are dancing at late-night playa raves, while the next minute, a man building a globe with days to go before the festival is worrying that his sculpture might decapitate someone — the camera-work is shaky, the editing random, and while much of it focuses on people talking ethereally about how awesome Burning Man is, we never spend enough time with any of them to see their point, instead trudging along with post-fest volunteers picking up cigarette butts and bottle caps (a rare concession to reality in this almost two-hour-long commercial) and dispiritedly digging holes in the sand to help secure a crumbling papier mache sculpture. The film is populated like a senior class slideshow, where, despite all the talk of community, no one’s making any actual effort to tell you about the in-jokes. (Why is that old man yelling about glue, and why is everyone convulsing in laughter? Why include such a long segment about how the people in the RVs have to perform ruthless checks of crammed closets and below-sink crawlspace under their tanks for stowaways who don’t want to pay the $250 for tickets when no one ends up finding any such stowaways?)

The fun, censored of sex and drugs, is too clean to even be called fun. Participants talk earnestly about how “it’s all about survival,” how they’re “meant to do” things that end up “coinciding with the world in some way,” and how they “move toward what feels most real.” Like, it all just happens, man, and while you’re going to your job in your SUV and slacks, we’re being “kindred spirits” experiencing something “organic.”

“There is something in the energy that provokes reverence,” an attendee says, as we watch slow motion footage of people dancing in dust devils. Another adds: “It’s more profound in the playa.” They talk about “convergence.” They are starry eyed, good-hearted dandelions floating in illusions of illumination, “converging” like lotus-lit middle management. Talk about a bad trip.

And see, that’s the thing. I don’t loathe these graying Gen Xers for having a good time. I loathe the sentiment — in choppy PR style, no less — that they are so good for doing whatever it is they’re doing out there. That they’re better because they can pretend they are bold for displaying boobs and anti-war slogans and wearing glow-sticks in your hair among 50,000 others who are almost guaranteed to be totally on the same page as you politically, socially and culturally. There’s no adrenaline. No fear. No risk of anything bad at all happening to you. There are restrooms and medical facilities. There’s sculpture. And coffee. And gluten-free burritos. And ice. You might as well go to Sedona.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.