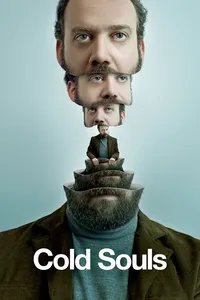

Cold Souls

We use the word “soul” so often in conversation, describing some things — telemarketers, TV evangelists, Walt Disney World, airport Chili’s — as soulless, others — Johnny Cash, Weegee, Donizetti, a fine oxtail stew — as soulful, or having soul. A company that could trade in souls, could extract them more easily than wisdom teeth, buy and trade them across the Atlantic like leaky balloons of coke, and one man’s misadventure with said company, would seem to be a topic as explosively fun as deep and probing. “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless

Mind” did that in an imaginative, heartbreaking, beautiful way six years ago, with the topic of memory. “Cold Souls” not only doesn’t even come close, it — at times — makes one wish they could avail themselves of the memory-erase procedure employed in “Eternal Sunshine.”

“Cold Souls” is a small movie that dithers around great themes and great actors. Paul Giamatti, playing a New York actor named Paul Giamatti, is feeling frustrated playing the role of another frustrated man, Uncle Vanya, on stage. Pretty meta, huh? After reading a wry “New Yorker” article (are there any other kinds?) about New Yorkers unburdening themselves at a new soul-extraction business, Giamatti signs up. Soulless, he shocks his wife’s friends by blurting out during a dinner conversation about a brain-dead relative in the hospital that the friend should just pull the plug. And that’s about as far as the “what’s life without a soul?” thread goes before the

audience is distracted by a completely improbable subplot in which a hot young woman throws herself at the unlikeable Giamatti the character, not the actor Giamatti). We’re supposed to be paying so little attention that they even have the soul-extraction doctor — carefully speaking in soothing rhetoric up to this point — refer to

soul “trafficking” and soul “mules” as legitimate parts of the business.

The movie further devolves with a series of vignettes about suicide, motherhood, orphanages and the nature of the child inside the man, which culminate in an icky scene in which Giamatti must “look inside” to “re-connect” with his soul, exactly the kind of fuzz geared toward astrologists and angel-believers that ruined last year’s

computer-animated “9.”

“Cold Souls” is a dud, though one might be fooled away from thinking so due to the heaps of clams spent on the fancy white soul-extracting medical devices, the Roosevelt Island tramway shots, the cavalcade of scamming Russian cuties and main character Paul Giamatti (who holds our attention and our sympathy as a despairing actor and husband dissatisfied with his success in both realms). And, note to writer-director Sophie Barthes: An agonized couple walking away in soft focus on a cold beach is probably a worse ending than the he-grabs-her-and-kisses-her variety. Show me a movie that couldn’t, conceivably, end with two troubled people walking away on a beach.

And combined with the daydream sequences, the frequent shots of Giamatti wondering about the nature of his soul as he stares out at the ocean, or at the frozen Neva river in Saint Petersburg (a place he never, by any rational convolution of the plot, should have shown up in the first place) and the tortured-artist-meets-muse plot that was overdone when Woody Allen had a shot at it? If there were a drinking game for film school cliches, you’d have alcohol poisoning by the time Giamatti moans, “I just want my soul, with all its imperfections and

darkness!”

The cleverness that seemed, at first, to imbue the movie with the hue of originality, that would say something new about humanity, is, upon further inspection, no bigger than a garbanzo. And like its main character, when the movie looks inside, everything falls apart.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.