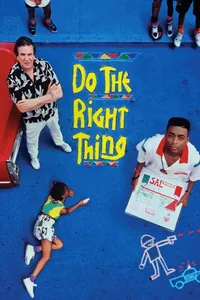

Do the Right Thing

Vicki Lawrence dressed as an old lady, keeping her wacky redneck family in check in “Mama’s Family,” was about as risque as approved viewing got when I was a kid. It was time to change the channel to the “Frugal Gourmet” or, heaven help me, the “MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour,” if the Cosbys started dancing across the screen. We were just that white.

So it’s no surprise that it took the 20th anniversary edition of “Do the Right Thing” to see a Spike Lee joint — apart from 1999’s “Summer of Sam.” Which is too bad, because “Do the Right Thing” is one of the hardest kinds of movies to make well, a message movie. It could have turned out so, so execrably bad. Bad like the “Saved By the Bell” where Jesse Spanno gets addicted to — gasp — caffeine pills while cramming for geometry and a dance-off.

Two decades later, “Do the Right Thing” only shows its age in its gigantic boom boxes and fad fashion. (You wanna snicker at Rosie Perez doing the cabbage patch dance in a red jersey dress, red tights and blue high-top sneakers? It’s your funeral.)

“Do the Right Thing” combines the energy of a mid-century stage production of “West Side Story” with all the edge of Tarantino (if not the soundtrack diversity — Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” provides the bulk of the tunes, even though “Sam” Jackson, as local radio DJ Mister Señor Love Daddy, has a great monologue list of musical greats). There’s shock without a profusion of four-letter words, violence without gunshots, and a gentlemanly neighborhood drunk called Da Mayor delivers the title in some off-hand advice to pizza boy Mookie (played by Lee himself).

Most importantly, everything else comes first: the story of a summer’s hottest day, the brownstones and sidewalks of Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood — one brick wall tagged, “Tawana (Brawley, who alleged rape by policeman) told the truth!” — the Puerto Ricans, Koreans, lone Irishman, Mookie’s Bensonhurst Italian bosses (John Turturro and Danny Aiello, wearing a cartoon saguaro-printed shirt) all clashing with the neighborhood’s blacks, most of whom are “30 cents away from having a quarter.” The anger — Brawley and the 1986 Howard Beach racial attacks are only briefly alluded to — explodes in a member of each group shouting a hot stream of racial cliches and epithets, one after the next.

It’s not phony. It’s not preachy. It’s earnest, full of life, unafraid, fed-up and hopeful. It’s not even obvious there’s a message until the movie crests a hill and the end crashes down like a roller coaster ride. Among the fire and screams and anger of the final scene, Spike Lee is clearly saying that one can pick a path of peace or a path of violence, and you could argue either one’s righteousness.

Too bad, in 1989, in suburbs across America, white faces would look down at the dark faces looking up from the video jacket at their local rental store and never mull picking it up. Whatever was inside was too hot, they thought. Whatever was inside, they didn’t want to know or care about. Which was, really, sort of the point of the movie. As Sam Jackson would say, “that’s the double truth, Ruth.”

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.