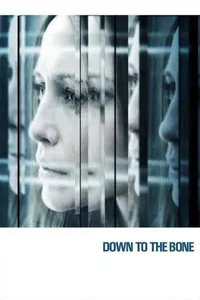

Down to the Bone

The average filmmaker can’t make mainlining coke mainstream. Unless you’re Danny Boyle, you can’t make a heroin user heroic. Unless you’re John O’Brien, who wrote “Leaving Las Vegas,” your characters are going to be gritty — but not in a filthy way. They will be charismatic, but their manipulations won’t hurt the people around them, not too bad anyway. As the audience, we have to like them.

We like Irene, the main character of “Down to the Bone” because she Sharpies her tooth black to be a witch and trick or treat with her kids, even though she has to snort a line before they get out the door. We like her because Vera Farmiga is beautiful and has just the perfect look of revulsion on her face when her sons’ father comes in the door holding a six pack of beer in the base of a toilet.

Written and directed by Debra Granik, who also did this year’s “Winter’s Bone” (a slightly better bone-centric name for a movie) “Down to the Bone” is a mostly accurate depiction of the way being broke and overworked and depressed is. Unfortunately, it correlates that world too closely with being broke and overworked and depressed because you’re a junkie. The ghetto of addiction is populated by people from every income bracket. The pill-dealer slinging wafers in the doorway of a suburban home and rushing off — “Nah, I can’t stay. It’s Turkey Day. Crazy busy” — he delivers in every neighborhood, not just the ones with plastic sheets on their windows. The kind of people who throw their lives away on drugs are people.

There’s something else. Irene’s remarkably restrained for someone willing to stick a needle in her arm. She can still feel shame. While her kids wait in the car and she goes in to score (her sleaze bag dealer pulls back a giant American flag in the window to see who’s at the door) and she’s short cash? She doesn’t pull down her pants and offer alternate payment. And he doesn’t ask her. When she finally goes to rehab, there’s more boredom than withdrawal; in one scene, women sit on a couch in front of another woman plugging away on a Stairmaster, staring blankly at a painting of a kitten in a coffee can.

Yes, drugs cost her her job. Yes, drugs cost her her car. Yes, at one point her kids are sort of horrifyingly fed peanut butter and jelly on un-toasted bread by mom’s bathrobe-wearing boyfriend.

But more often than not, after the predictable dramas of junkie life unroll, the story pulls Irene away from the edge. Money comes through. There’s still fresh milk in the refrigerator. There’s no screaming, no violence. Irene clearly hurts. She clearly loves her kids. She clearly knows she is effing everything up beyond repair, day by day. But the only feeling of hers that really goes “down to the bone” is that she cares about the next high more than any of it. She gets close to the bottom. “Down to the Bone” gets close to it too. At the last moment, both of them flinch.