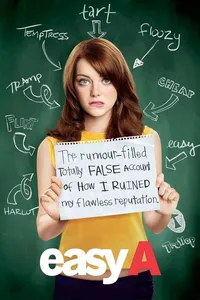

Easy A

Don’t hate, but “Easy A” was really entertaining.

In the tradition of American teen movies taking on classics (with sassy results, like “Clueless” and “10 Things I Hate About You”), “Easy A” takes Nathaniel Hawthorne’s ponderous, mopey “Scarlet Letter” and re-tells it in a smart, sweet, sun-drenched, modern-day California high school.

If you managed to stay awake in high school English class, you might remember that the besieged American woman Hester Prynne, who dared to sleep with a man (resulting in a pregnancy) when her husband was lost at sea was forced to a life of near-constant misery, with a Star of David-like badge of shame, a red “A” pinned to everything she ever wore, to remind the Puritans around her that she had committed, gasp, adultery. Hawthorne writes that the A was Prynne’s “passport into regions where other women dared not tread.” Miserable regions, of course, like public shaming, the inability to enjoy even the sunlight on her skin and townsfolk trying to take away her daughter. (The guy she cheated with, a minister, is gifted with the ability to deliver ever more powerful sermons.) Nice, huh?

In “Easy A,” the situation is completely, refreshingly different, thanks much in part to lead actress Emma Stone’s total owning of her naughty reputation.

Stone, as the cynical-and-loving-it Olive, actually hasn’t done anything, but you know how rumors spread. In “Easy A,” they spread with surprisingly beautiful continuous shots, camera speeding around hundreds of high school students, pausing in slow motion to capture their reactions to seeing the gossip pop up on their smartphones.

Olive, a girl whose beautiful body is “invisible” to her classmates because of her smarty-pants personality, suddenly starts being noticed when her classmates think she’s getting it on. “Easy A” owes less to the fraught, terrified morality of Hawthorne and more to the fearless, pounding, Whites Stripes-worthy sentiment of Loretta Lynn, in her song “Rated X.”

“Nobody knows where you’re going but they sure know where you’ve been,” she sings. “All they’re thinking of is your experience of love — their minds eat up with sin. The women all look at you like you’re bad and the men all hope you are. But if you go too far you’re gonna wear the scar of a woman rated X.”

Indeed, instead of becoming drunk on the attention of boys and the buzz of whispering gossip, Olive decides to better her position, and that of the other students on the lowest social rung. Her frame of reference is strong enough: everything from Lillian Gish’s “Scarlett Letter” to the 80s classics of John Hughes. She conspires with a gay friend to tough out the rest of high school fabulously, telling him, “You’ve got to do everything you can to blend in or decide not to care.”

With “an incontrovertible sense of humor,” in her mother’s words, Olive is making the same decision, figuring out what it means to be labeled “a dirty skank.” Does she become a skank? Backtrack and disappear? Or own it with raucous, Mae West retorts, sunglasses and black corsets with a red A safety-pinned to the lace — satirizing the aghast crowds around her by making fun of herself first? Of course — of COURSE — there’s a cute guy she likes (he has the one tone-deaf, prime-time sit-com, kids are never going to talk this way line: “see you in the salt mines”).

Probably no one would have given the movie the green light without the puzzle piece hunk. But what makes the movie work is that he isn’t her motivation to make her situation great. She is — no matter what the status of her virginity is.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.