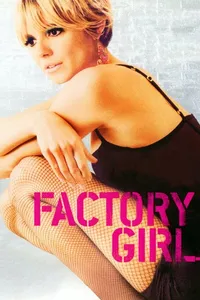

Factory Girl

Poor Edie Sedgwick, the subject of “Factory Girl,” she died at 28, you know? She slashed the wrists of her soul on the sharp tin edge of pop-artist Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s soup can of fame. She was wooed by the limelight of the late 60’s and got all burnt up like a piteous moth.

She was Tragic, Troubled, Tormented and Tanked with a capital T.

She was a waste: Totally.

And “Superstar” Sienna Miller’s evocation of Edie Sedgwick might well be the pinnacle of her career, when it’s all said and done. Miller herself may be seen in the popular media for nothing more interesting than her proclivity to throw together questionably-edgy, leggings-dependent outfits, but my heavens - girl’s got talent on the magnitude of Johnny Depp’s Hunter S. Thompson in 1998’s “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.” For Sedgwick, Miller tapped in to something junkie-dark, something hardly aware of its own fast-ticking will to destruct, something that is not her. Something that made her look ugly enough to chill a toad.

But, bottom pimpled with needle marks, lipsticked mouth reeking of a morning-after bar Dumpster, voice lilted in that old-money, “Grey Gardens,” summer-in-the-Hamptons sigh and roughened by fingernails and stomach acid, born with enough dough, raised with enough sex in the air to permanently fry her psyche, and aware of the world just enough to know that if she’d lived past 30, her kilo-weight chandelier earrings would make her earlobes sag past repair, one seems hard pressed to say why “poor little rich girl” Edie Sedgwick deserved a shrine of a movie like “Factory Girl” in death, instead of a good spanking in life.

America loves girls like Edie Sedgwick far more than the Anna Nicoles and the Britneys who scrapped it up to the top and then teetered there. America loves more than anything the empty-headed piffle Paris Hiltons and the Cory Kennedys, who are free enough to work 40-hour therapy schedules, dumb enough to be stumped by self-serve soda fountains, and think check-engine lights are mixed drinks. And talented wage-monkeys people behind the camera and prop masters with a keen eye to eBay’s vintage department can make a movie like “Factory Girl” look good, make it sound good, keep the dialogue and the color clipping along, and make it look really real, but ten-to-one odds says if you get a clench in your gut and check the calendar twice when you’re paying rent - and that makes about 190 million of you - you’ve got to wonder what the point of it all is.

America loves calls for help, as long as they’ve got endless credit. We love waifs who cry, as long as they strike a hip silhouette while they blow their inheritances. We’re interested by debutantes who gobble black pills and set buildings on fire with their cigarettes, as long as they can giggle sound-bytes when they wake up.

Henry David Thoreau once said that lots of people “are concerned about the monuments of the West and the East - to know who built them. For my part, I should like to know who in those days did not build them - who were above such trifling.”

We love the trifles. Enough, sadly, that we gotta make movies about them. It may be 2007, but we still dig the pyramids. And a lot of us help schlep the bricks, as it were. Andy Warhol said in the future, everyone would be famous for 15 minutes. Had he lived today, he might have said in the future, everyone would have a movie made about them. Had he realized there was a world outside the Factory sphere, he would have had a footnote.

There’s a scene in the wretched sci-fi kiddy flick “Santa Claus Conquers the Martians” where Santa Claus, when asked if he’d be able to deliver all his toys on Christmas, says, “Well, we’ve never disappointed the kids yet!” In the “Mystery Science Theater 3000” satire of the movie, Crow, a bot, counters that with, “Except for the poor ones.”

What Warhol really meant was, in the future, everyone will be famous for 15 minutes. And have books written about them, photo montages lovingly printed and matted, fan site code hacked together to clog the tubes of the internet, YouTube collages made, and yes, movies filmed and preserved for all eternity. Everyone - except for the poor ones.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.