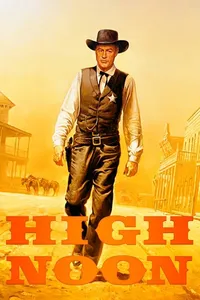

High Noon

What do you do for the 90 minutes after you’ve said your wedding vows?

If you’re Will Kane (Gary Cooper), the marshal of a small town in territorial New Mexico, you hand in your badge, whisk your doll-like Quaker bride Amy (Grace Kelly) out of town because you’ve just heard the town’s baddest bad boy has been pardoned — and then man up to the threat and return, confident that a posse will take just seconds to whip together. Instead of pondering wedding reception food and the other pointless niceties of the terrible modern wedding, you consider who kills and who should kill.

That’s just in the first 10 minutes of the surprising, bristlingly cynical, 90-minute “High Noon,” (1952, not rated).

On the edge of town, bad boy Frank Miller’s henchmen are waiting at the train station, eyes on the horizon like dogs waiting for their master to come home. When the noon train pulls in, they’ll get their revenge on the town that put their leader away — but on the news that Miller is returning, a number of the residents, including the town judge, and sultry store-owner Helen Ramirez (Katy Jurado) are planning to flee on the same train.

Even Amy plans to go, refusing to be a widow on the same day she was made a bride: “You know there’ll be trouble,” she tells Kane. “Then, it’s better to have it here,” he says, apologetically. (And he is sorry. As Amy explains to Helen, who argues dispassionately that she should stay and grab a gun for her man, “I’ve heard guns. My father and my brother were killed by guns. They were on the right side but that didn’t help them any when the shooting started. My brother was 19. I watched him die. That’s when I became a Quaker. I don’t care

who’s right or who’s wrong. There’s got to be some better way for people to live.”)

Not everyone’s leaving. The barber, for instance.

“How many coffins’ve we got?” he asks the coffin-maker, who tells him “two.” The barber responds: “We’re gonna need at least two more, no matter how you figure. You’d better get busy, Fred.”

But Kane is getting desperate. He punches out a bartender, then interrupts a church service, where one of the congregants points out that he’s not even the marshal anymore. It’s this scene where “High Noon,” despite being a Hollywood western with an orchestral score and top-dollar stars, gets real — and a little surreal. Those in the

church decide this isn’t a conversation children should hear, order them out, and they go clattering and laughing down the stairs. Another adult tells Kane he should have locked up the bad boys at the train station on sight — old West justice, you might say — but Kane recoils, saying they hadn’t committed any crimes yet.

Finally, the minister lets Kane down: “The commandments say ‘Thou shalt not kill,’ but we hire men to go out and do it for us. The right and the wrong seem pretty clear here. But if you’re asking me to tell my people to go out and kill and maybe get themselves killed, I’m sorry.” Quickly following is the mayor, as hilariously dark as the barber, worrying about what people will say about a town that’s just recently gotten back to being “decent” and “growing” — a position far more jaded, but understandably so, if you’ve ever listened to a border mayor speak candidly about their relationship with Santa Fe: “Now, people up North are thinking about this town — thinking mighty hard, thinking about sending money down here to put up stores and to build factories. It’ll mean a lot to this town, an awful lot; but if they’re gonna read about shooting and killing in the streets, what are they gonna think then?”

He leaves, dispirited. His chances are looking grim. His wife is still sitting in the hotel lobby, waiting for the train. He’s got nothing. Even his old mentor tells him, “Down deep, they don’t care. They just don’t care.”

This is a triumphant American Western, of course, so it’s not like Kane will lose the fight we know will happen. In fact, what he does next, in a time when most of us would be our most frantic and hoarse-voiced and sweaty, is more effective than the typical action sequence of oily guns being loudly loaded. He gets a shave. He accepts the frantic resignation of one special deputy. And, as the camera shows us a glimpse of the penitent on their church pews and the drunks sitting anxiously on their bar stools, it shows Kane, writing a will. We don’t have any idea how, but we know one thing at that point: he will not need it. Not today.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.