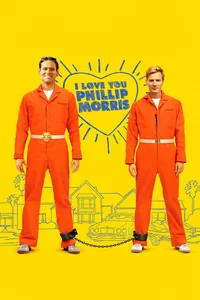

I Love You Phillip Morris

A tour de force by Jim Carrey and Ewan McGregor, “I Love You Phillip Morris” (which has nothing to do with the tobacconist) was box office poison. McGregor (“Trainspotting,” “A Life Less Ordinary”) tried to explain to “Out” magazine why the gay romance/white collar crime caper left a bad taste in so many people’s mouths: in the world of Hollywood blockbusters, he said, “they’re really reluctant to step out of any box, which is why the movies become very bland.”

It’s the story — the true story — of Steven Russell (Carrey), a Southern police officer and family man who never looks happier than when he’s pounding out a hymn with the church choir. Well, except for when he’s pounding away at another sweaty man. After a near-death moment, he decides to be open about his sexuality. But to finance the lavish lifestyle he wants, he obtains a stack of phony charge cards and enters the world of small-time slip-on-a-grocery-store-puddle insurance fraud. It’s when he’s caught and we meet him as a long-timer in prison that we suddenly care about him. He’s giving a tour to a new inmate, flippantly explaining the barter system, which boils down to “everything can be had for enough money or oral sex,” when a fight breaks out in the yard. Russell stops to look. Moving behind the brawl, looking worriedly at the maelstrom, is a young, golden, worried McGregor, the sun’s rays lighting up his bright yellow jumpsuit like melting margarine. They fall in love. They’re separated. They manage to exchange long, tiny-scripted letters, Abelard and Heloise style, and to finally end up as cellmates. Love behind bars is a punch line for mental lunks who think reading books is for sissies. But this is not a love story about rapists and pansies — it’s one where Johnny Mathis’ “Chances Are” plays over a love scene that manages to be tender and somewhat black-hearted, as the camera moves from their nest

to linger on a rowdy inmate confronting a gang of stun-gun-armed guards.

In between jail stints and fantastic, swift escapes, Russell manages mighty turns as a lawyer and a CFO, fooling everyone. Morris, however, is not pleased about being one of those fools. Morris finally confronts him, his voice soft and steady, his brow furrowed under his sun-blonde bangs. His lines are wounded, but he plays them without a hint of temper tantrum — a wholly original delivery of a scene that, screechy and accusing, we’ve seen in a million hetero romances.

“How can I love you?” Morris says. “I don’t even know who you are. And you know what’s sad? I don’t even think you know who you are. So how am I supposed to love something that don’t even exist? You tell me.”

Steven Russell doesn’t realize or articulate the answer to this, but one could say the answer is that, really, few of us know who we are. Steven Russell arguably knows who he is because he knows what he wants: enough money for fine clothing and champagne and flowers and blow jobs on the deck of a million-dollar yacht, the freedom to fly high with the love of his life. Like everyone else in the whole damn country.

The end of his story is not unexpected, and somewhat dispiriting, but leaves us — nobly, I think — with the idea that even if Steven Russell is not a hero, the idea that Steven Russell represents is heroic. Really. Had he done what he did with more friends in high places, with a good name on his birth certificate and his MBA, he’d be a high-paid consultant finding and correcting the weaknesses in our nation’s security systems, lavished with stock options instead of solitary. When the petulant financial potions masters and their want-for-naught politician puppets, the slumlords and slavedrivers and medicinal-industrial complex combines that harvest and thresh our

paychecks in sickness and in health — the system itself — screw over Americans, that is the very definition of winning, at least when it comes down to cutting the checks. But when one American whose above average intelligence places the pursuit of his own life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness above following all the rules all the time screws the system, he’s put in maximum security for several lifetimes over. The difference isn’t that Russell was queer, or exceptionally subversive and dangerous. Maybe the difference is just that no one could ever take a cut of it.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.