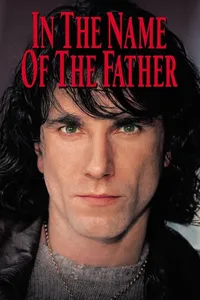

In the Name of the Father

An angry rock song builds as a group of young people walk happily into a pub one October evening in Guildford, England, in 1974. The door shuts, and the windows and walls explode with fire. But as the nightmare of “In the Name of the Father” unfolds, we learn the five people inside aren’t the only ones whose lives are destroyed by the IRA bomb. Thirty miles away, in London, two young men from Belfast, Gerry Conlon (Daniel Day-Lewis) and Paul Hill (John Lynch) have given their last coins to a homeless man. Conlon, sent to London by his father to escape a kneecap-shooting by the IRA for being a scrap metal thief, is already bitter and beleaguered, clouded by his father’s disappointment and his own shortcomings. When he and Hill luck into an easy £700 burglary, they find a way to return to Northern Ireland at least wearing nice clothing and flush with cash. What they don’t expect is a London acquaintance telling officers that the two frequently talked about the violence in Belfast, and had just returned there with “a lot of money.”

“In the Name of the Father” is jaw-dropping and heavy, and comes just four years after director Jim Sheridan and Day-Lewis had collaborated on another formidable biopic, “My Left Foot” (my review here).

Emboldened by a new act that allowed suspected terrorists to be held for seven days without charges, Hill is arrested, then Conlon, at gunpoint from his own bed at night, and other arrests follow, include that of Conlon’s thoroughly innocent aunt in London, her children, her husband, her brother, a friend and Conlon’s father, Giuseppe (the recently deceased Pete Postlethwaite). The officers rough up Conlon just enough to not leave any marks (scalp-grabbing features prominently), tells him the others have confessed and implicated him, and in a grueling and painful scene of questioning, ask and re-ask for timelines — an interrogative bootcamp tire drill — and for facts they don’t know. “Who is Marian?!” Neither the audience nor Conlon knows the answer to that one, but by the time he’s had it screamed at him for the 20th time, we’re dying for him to come up with one. Finally, he’s given a “confession” to sign.

“Will you have the bomber?” one officer asks another, as the torture wears on. The response from the other officer is a non-answer, an evasion made out of desperation, but one with the chilling power of the government behind it: “Our job is to stop the bombing.”

Passion, anger and grief, not evidence, rule the trial, and spectators scream for hangings at the announcement of the heavy sentences for those accused. The audience, like Conlon and his co-defendants, are the only ones who know what actually happened, but in such a setting, the truth might as well be something on the bottom of the sea.

“It’s OK, Da. I actually loved that Chumbawumba album.

Based on the autobiography “Proved Innocent,” in Conlon’s words, the case in “In the Name of the Father” “was so insane that if you made it up, nobody would believe it.” It even makes difficult fiction, unless saturated with absurdity, science fiction and humor like another terrifying tale of wrongful imprisonment of a suspected terrorist, Terry Gilliam’s 1985 classic “Brazil.” In the U.S., with CIA torture going unprosecuted and both warrantless surveillance and the detention — indefinite, not just for seven days — of citizens suspected of terrorism sanctioned, the lessons of “In the Name of the Father” are as important as they are, sadly, unheeded.

And this story, with Conlon’s eventual vindication, 15 years later, relies on fragile, but vital threads of evidence uncovered by defense attorney Gareth Peirce (Emma Thompson) — evidence not given up by a government interested in transparency, but passed into her hands in error. After all that time, we’ve only seen Conlon walk a few of the concrete circles out of millions he must have paced in prison. He has cigarettes, mail, posters on his wall, but the cell for an innocent person can’t be made comfortable. It’s not the concrete and the bars and the threat of violence that would truly erode your spirit, but knowing that the system has failed in a vast and obvious way, that bloodlust can so easily cause good people to howl like angry mobs, and that officials can feel justified in throwing aside the rules of civilization in their zeal to combat “terrorism.” Chillingly, such “kill them all and let God sort them out” tacts would seem to indicate to actual terrorists that we have no damned idea what we’re doing. But outcomes like Conlons are what we should expect when we include in our arsenal such weapons of idiocy as chaos and hubris.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in the theater anymore. She lives in North Hollywood, near the In-N-Out Burger.