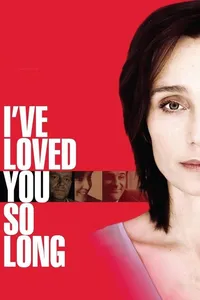

I've Loved You So Long

To say that “I’ve Loved You So Long” (2008, PG-13) is another foreign film about disappearance is like saying that “Ed Wood” and the new “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” are both just Tim Burton movies where Johnny Depp makes interesting costume choices.

One would be advised, straight off, to ignore the sappy title, which comes from a line in a song the sisters played together on the piano when two sisters were little. When we encounter the two, the older one, Juliette, has been in prison for 15 years for murder. Lea, the younger, has gotten married, taken a job teaching university literature and adopted two Vietnamese girls.

Like the audience, Lea fully accepts and forgives her sister first — forgiveness will come later. And as in real life, we tiptoe around the subject of the murder until almost the end of the film — after Lea’s husband explodes when Lea tells him Juliette is watching their girls for the afternoon; and after the manager of the factory where Juliette’s gone to get work orders her to simply “get out” when she finally tells him (and the audience) for the first time whom she murdered — her 6-year-old son.

While most of the movie swaddles Juliette and her thousand-yard stare within the cozy family home, the Lorraine countryside and a network of social, welfare and police workers making sure she’s becoming a productive member of society, there are a few tense moments in which you wonder if Juliette will squander her sister’s — and the audience’s — trust. She snaps at one of her nieces, who wants to read her a poem. When Lea asks softly, “did you think of us ‘inside’?” Juliette barks, “it’s called prison!”

At the same time, though, the movie encourages the viewer to wait before passing judgment. A police lieutenant, pondering the Orinoco river in South America, notes, “we think we know everything, but we don’t know the source of a river.” Her sister’s co-worker, Michel, who used to teach in prison, remarks on the “fine line” between inmates and civilians, even as Lea, in the next scene, rails at her Dostoevsky-reading students that “not every murder contains its own redemption.” The reveal comes after a scene in which Lea is on the phone with a physician friend, silent, as her oldest daughter reads aloud to herself from a fairy tale. A magician is warning a prince about the coming night, where “you can’t tell the shadow of a dog from that of a wolf.”

In the end, Juliette puts words to what is visible on her throughout the film: “The worst prison is the death of one’s child. You never get out of it.” Though it’s vital for the audience, Juliette cares not whether she’s seen as wolf or dog; to Juliette, it is a permanent nightfall.