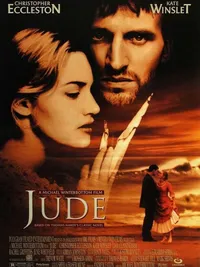

Jude

Beautiful Sue, regal in a long white Victorian gown in one moment and sexily tossing back ale and smoking cigarettes in the next, buys a statuary of a naked Jesus and grouses a bit when a superior finds it, smashes it and stomps it into bits in the ground.

We are similarly smashed, stomped, pulverized at the end of “Jude.” The adaptation of 19th century heavyweight Thomas Hardy’s “Jude the Obscure” makes the bulk of modern drama look positively like red ochre daubed against cave walls.

Oh, you’d be forgiven to think this is lightweight, melodramatic stuff, this 1880s romance, an excuse to show off the emerald green of England’s fields, the fine antique stonework of its quaint college cities, Kate Winslet’s bosum in a figure-hugging corset and your token busty country girls getting their petticoats soaked scrubbing up in a babbling brook.

No. The sudden love of an aspiring scholar — Jude, played by Christopher Eccleston — and teacher Sue, played by Winslet — is forbidden, because although they met as adults, they’re cousins. They simmer next to each other. He reads Catullus: “the man who sits at her side, who watches and catches that laughter which softly tears me to tatters. Nothing is left of me, each time I see her.” Rain-soaked Sue changes into some of Jude’s man’s clothing and curls up with his pint bottle of brandy in a tiny stuffed chair, and nothing happens but that simmering. They marry others, out of duty, and are miserable, and finally manage to extract themselves.

Briefly, there is glee, and they run on the beach, flogging each other with ropes of kelp like children. After months of stifling hesitation, there are children. Sue and Jude vow to endure rainy evictions and unjust firings “as long as it takes for the world to change.” They cannot, however, impress that vital truth on those to whom it matters most. Death comes — more horribly than fiction can imagine.

The force of Jude is how wicked its world is, how, raw, throbbing with shadows and far-too brief glimpses of happiness it is. “Jude” is also a lesson in curses. The religion Jude and Sue are reasonably skeptical of (and which expresses doubt in itself, Jude notes: “For who knoweth what is good for man in this life?—and who can tell a man what shall be after him under the sun?”) which is supposed to give the downtrodden hope and meaning, instead rapes them at their most vulnerable.

Education, which earlier, gives Jude the power to, prompted by a heckler, down a shot of whiskey and climb atop a college pub table to shout the Apostles’ Creed in Latin (“You bloody fools,” he finishes. “Which one of you knows if I said it right or not?”) gives him the ability to recognize when his far superior abilities are snubbed and smashed by the jealous, close-minded pigs in power he confused for intellectuals.

Love — its expression — earns Jude a partner, a mother, trust, intimacy, joy, but also the hatred and punishment of a world who might as well have their noses in a corner.

Relatively speaking, Jude is obscure, yes, and so is his fight, and so are all of our fights. What’s important is that we don’t put down our fists, that we keep knocking on doors until we find shelter, that we keep moving, that we stay firm in the knowledge that the storm will pass — and that we teach the same. At the end, on the worst Christmas one can imagine, Jude is at his most weak, alone, looking away, surrounded by white. He screams something powerful. He is alone. But we know, and so does he, that his message was heard by its intended target.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.