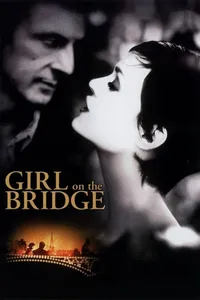

La Fille Sur Le Pont

Hardscrabble sometimes-con Gabor the knife-thrower can’t resist the girl on the wrong side of the Paris bridge. Neither can we. Though we’ve already heard Adèle describe herself as being like fly-paper, a sexpot with a touch that turns things to sour, she’s no confused, whining victim, and cries not because she wants a magazine-shiny marriage to sprout out of meaningless sex, but because she’s convinced she’s sitting in life’s train station, watching people rush by, and eventually her train will arrive.

That might sound like delusion to most people, but to Gabor, a knife-throwing ladies’ man who’s already been banned from his share of casinos, it’s an intuition. Perhaps that’s why we’re willing to accept Adèle’sacceptance of him as her employer, life-changer, sugar-daddy, savior. As so often happens in stories, she’s not the only one who ends up grateful and in wonder of the meeting. He may be the one with the knives, but in dialog - even translated from the French - the two almost immediately enter into a tango of words so masterful it never stumbles over the line into gaudy (je suis désolé,* “Moulin Rouge”!)

From beginning to end, we wonder about the two things any audience - in the theater or in real life - would ask when gazing up at a girl on a bridge, or a guy throwing knives. Will she jump? Will his knives fail? And you’d be right to think, without seeing the movie, that if I gave away the answer to either, that would puncture the magic of the movie. But she does jump. A knife does finally stab into flesh. And I’ve given away none of the good stuff, I promise. That’s how much magic this movie has hiding up its sleeve. Clean underwater nighttime shots are stabbed through with angelic light, while a shot from a fly’s perspective soars even in a hospital hallway. The cinematic contortions are as fluid as a man in a full-body leopard-suit, the wit as sharp as the whizzing tips of Gabor’s knives, the perfume-commercial beauty as glittering and perfect as Adèle’s wet curls. The soundtrack will make you want to spin in circles or sob, and, fittingly for its model lead actress, almost every velvety shot could sell Chanel perfume as a still.

This is quite possibly the most enchanting film I’ve seen since “Amélie” - and in its knife-throwing scenes the most seductive power grab of a woman in a vulnerable position since the world met Jessica Rabbit slinking out of the Art Deco curtains in the Ink and Paint Club in “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?” Consider me bruised by its hard edges, stabbed by its tenderness, in stitches from its sexy humor and bleeding - just a little bit - from its hidden edginess.

Usually, I hate men coming to the rescue of damsels in distress. In a world where one rarely sees a reverse, I hate it when young, fantastically gorgeous women fall for older, craggy men. I don’t like exposition that goes into voiceover flashback without ever explaining why the story’s being set out that way. I think luck is a cheap gimmick. And I know suicidal depression is rarely something that one only needs to be guided away from once.

But, like Adèle, I can be talked out of things too.

Ashley O’Dell writes about movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.