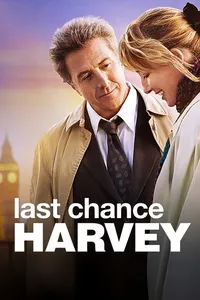

Last Chance Harvey

The movie’s called “Last Chance Harvey,” but it’s really divvied up more between the titular character’s ultimate shot at happiness and that of a certain Kate. Harvey’s a pensive piano composer in New York whose musical talents have been funneled into writing jingles for laundry powder, a task for which he’s still willing to be a workaholic, even on the weekend of his estranged daughter’s wedding in London. Across the pond, educated Kate tries to administer surveys to mostly rude, harried travelers at Heathrow Airport, while also diverting her paranoid mother’s calls about her new Polish neighbor, who she suspects is disposing of corpses in a smoke-belching shed.

There’s almost zero tension in the entire film, written and directed by Joel Hopkins, which is set up from the very beginning as following Harvey Shine (Dustin Hoffman) and Kate Walker (Emma Thompson) nearly missing each other — at the airport, in a taxicab handoff.

By the time they meet up again, at an airport bar, they’ve both suffered a domino of humiliations. Harvey, clearly out of the loop at a rehearsal dinner, sits in silence as his ex’s husband, James Brolin, grins gregariously and toasts, “I just want to take you all back to that wonderful holiday we all had in Rome and wish you, salute!” (Lucky for Harvey, Brolin has to foot the bill for what’s surely a $100,000 wedding at the royal-lineaged Grosvenor House, where a standard room costs $900, plus $63 if you have a car to park). Still, you can almost see Harvey doggy-paddling to keep up with what his family’s become.

Meanwhile, Kate, set up on a blind date, becomes a fifth-wheel when her young, handsome date meets up with three friends (two of them female) at a pub.

Harvey and Kate are frustrated, you can tell, because it’s obvious these are not Serious Problems in the grand scheme of things. Even worse, these are the only problems they’ve got — and with no joy to balance them out, maybe ever. When they finally meet up again, at an airport bar, Harvey tries to apologize for brushing her off earlier when she was in survey-taker mode. She sneers at his double whisky method of handling problems. He lobs one back about her white wine and beach read novel.

“Go away!” she tells him.

But he doesn’t, of course. He’s too tired. This random, beautiful, middle-aged woman is all he has to buoy him as he drowns.

No, “Last Chance Harvey“‘s not a double shot of black-label Johnnie Walker. No, the two main characters, one could say, messed up by not getting lucky early in their lives — as though that kind of Hollywood scenario is anything more than random luck. It’s more a chilled chardonnay and a beach read. It’s not going to punch you in the face, but neither does it encourage complacency.

And no, it’s not an “Intervention” type of hitting bottom. There’s no track marks, tears, trips to the street to score chemicals. In a sense, it’s worse, because this loveless, unhappy bottom appears — to outsiders — to be a comfortable life. “Could be worse,” one says, not realizing how loveless emptiness can ache like addiction. It’s worse, because most would encourage you not to risk a comfortable life for a 48-hour jetlagged courtship that can probably be blamed a little on jealousy of your ex-wife’s new husband, your estranged daughter’s iciness, and so on.

But though the message is dotted with romantic set-pieces — man impulsively buys woman evening dress for an impromptu formal night, couple stays awake till dawn dancing and admiring historic fountains, emotional couple reunites in front of ancient riverfront — the message isn’t safe. It’s classical. Make the decision to risk it, thou careful, dejected baby-boomer, “Last Chance Harvey” says.

“How is this going to work?” Kate asks.

“I don’t know,” Harvey tells her. “But it will.”

Jetted to England? Rejected by family? Fired by your corporate zombie masters? Grab onto lovely love and retire to bathe in a stream in a writer’s villa in Spain. What penetrates in “Last Chance Harvey” is the sense that — not despite of the cliche, but maybe because of it — his story isn’t singular. That thousands of boring, steady, gold-handcuffed American lives that could change for the better if just that reckless choice, that beach-read dream and that glass of chardonnay, were swallowed without fear.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.