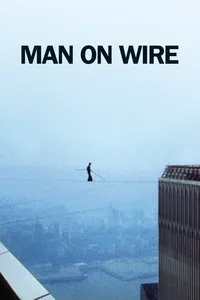

Man on Wire

For some, there’s a natural aversion to artists. Sure, you’ve got your Renaissance painters, with their commissions for church ceilings or portraits of sun-deprived, fat-thighed noble families and their Pomeranians. That’s a paycheck. But for most people — those without the disposable income to spend on flat-screen TVs, organic pancake batter in a tube or, hell, enough of your heating fuel of choice to get you through a New Mexico winter without a cardigan — art burns.

You think, “these people are eternal students, racking up low-interest student loans until their mid-30s waiting for some grant to save them,” or “these people are trustafarians, their parents burning through an ample retirement fund to keep them in sculpting supplies and tony lofts and espresso and sambuca and occasional junkets to Thailand.” You think, “these people would go crazy if they had to swallow their pride and take up a real day job.”

And most of the time, you’re right.

Thank goodness that black ballet shoe-wearing wire-walking Frenchman Phillipe Petit talks about mischief, not “art.” Thank goodness that, although Petit says near the beginning of the 2008 documentary “Man on Wire,” “my story is like a fairy tale,” he really sees his wire-walk between the two towers of the World Trade Center in New York as director James Marsh has put it — a “heist.”

Although we know how the movie will end — not only with his successful walk, but with the 26-years-later attack that would bring down the towers, there’s a surprising amount of tension in the movie, as Petit’s then-girlfriend and conspirators detail how they plotted the illegal wirewalk since before the towers were even completed. The reconstructed faux-documentary footage of the preparations are immaculately shot — the actors portraying the young plotters are spot on, down to their scruffy hair-dos and bell-bottoms. And despite the unfortunate and unintended parallels between Petit’s plot and the other illegal plot that would take down the two skyscrapers a quarter-century later, the unironic whimsy works — while giving the viewer an excuse to watch old Twin Towers footage without a whiff of impending tragedy.

Petit never talks about “exploring” anything “important.” After he’s arrested for walking the towers of the Sydney, Australia, bridge, he nicks the policemen’s watches and laughs, “who knows — and who cares?” when asked why he wanted to make the walk. He has more in common with Neal Cassady, Jack Kerouac’s speed-addled muse from “On the Road,” dreaming of wheels attached to his elbows to corner around hairpin mountain passes, or Evel Knievel leaping over Snake River Canyon a month after the WTC wirewalk, or Steve Irwin gazing with twinkling eyes into the face of a black mamba.

And, no lie, it helps that the young Petit and the actor playing him, the utterly cut 22-year-old Paul McGill, balancing on a practice wire across a French meadow in rumbled dungarees and wrinkled T-shirt, are gorgeous.

Petit is willing to operate outside the world of comfy schmoozing with check-writers. He is a cheerful lawbreaker. He is a fiercely intelligent and articulate hacker, a Kevin Mitnick with a marble-sculpted torso. He’s probably made a few in the global insurance and security businesses soil their drawers in the aftermath of his wire-walks. Good. People need ice-axes to break the frozen sea within, as Kafka said. Or, to paraphrase George Carlin, people need to be fucked with.

True, Petit never mentions who bankrolled his time, his travel, his matchstick models, his heavy wires — a gaping omission. He speaks about making every day of one’s life a challenge — and it’s somehow believable though we never see him breaking granite with a three-pound hammer, trudging a post office route or washing dishes during a third-shift restaurant rush.

Despite that, what makes Petit likable, admirable to installation artists and wage-slaves alike is that, even if the New Yorker is waiting to fete him afterward, what he does, he does like the most desperate of us — without a net.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.