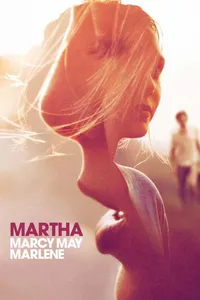

Martha Marcy May Marlene

There’s a parody version of the 80s show “The Wonder Years” out there that makes one small adjustment — taking away lead character Kevin Arnold’s voiceover narration. Called “the silent Wonder Years,” it drastically changes the tone of the show. Junior high aged Kevin is suddenly reduced to speechless awkwardness. When the camera lingers on him, instead of hearing his commentary, we just see a girl-crazy nerd on the verge of puberty looking like he can’t figure out what to say at all.

How you don’t want to end your trip to the Electric Daisy Carnival this year.

This is kind of what the beautiful-to-watch movie “Martha Marcy May Marlene” does, only for almost two hours, on a driving desire to be capital-S Serious that forces its audience to take part in an extreme humor-deprivation diet. Because we couldn’t appreciate the story of a young, motherless girl running away to a cult for two years unless we’re being beat over the head with overlong shots of haunted stares for minute upon shaky minute. For decades, it’s been established (best by Art Spiegelman’s magnum opus “Maus,” the biographical graphic novel about the Holocaust) that an author could — and should — include humor in works about serious topics, and that the ability to laugh with the prisoners at a little snippet of darkness in no way detracted from the audience’s willingness to sob in horror by the next page.

“By which I mean a new name, a starvation diet and some cleansing rape on the barn floor.”

On one hand, I want to thank the breathtaking Elizabeth Olsen (Michelle Tanner’s little, non-bizarro, non-billionaire little sister) for giving this movie depth and pain. On the other, I wish she hadn’t been cast as Martha (then “Marcy May” and “Marlene,” names assigned by the cult) — because an incapable actress would have made the movie unwatchable, and I could have saved myself the unilluminating glimpses into an incompetent upstate New York sex cult led by Madonna-veiny leader Patrick (a malnourished Charlie Manson type played by John Hawkes, a puke-worthy 30 years older than Olsen) and the roomy respite of Martha’s sister’s rented lakeside cottage, full of Crate and Barrel wine glasses and ready for your next J. Crew summer linens shoot.

Run as fast as you can in any direction if you ever hear anyone utter this phrase.

The problem is that writer/director/mumblecore Sundance darling Sean Durkin seems to have succumbed to a problem common among newspaper reporters, in which one gets so immersed in writing an intense article that it’s not until an editor looks at it that anyone notices the reporter forgot to say which court a murder trial took place in, or what the mayor’s first name is — not for lack of knowing, but because the story-teller sometimes knows the story so well they forget to tell their audience. Reading the script gets rid of a lot of basic confusion in the movie, but while it establishes certain plot points (where certain cult members go at night, Martha’s growing paranoia, why we recognize a man in a white T-shirt) it doesn’t explain any of the big questions. Without telling the audience that Martha’s reticence is completely realistic agony, it’s sickeningly easy to accept her as a petulant child who deserves to make her own mistake, and won’t appreciate any help given to her. But really, in the hands of Olsen, a rising star with tremendous potential, Martha is in so much pain, so much shock, that it’s unlikely she can even separate herself from her abuse enough to describe it in words the normal world understands, like “rape,” “starvation,” “murder,” and however one describes why nastily virile cult-leader Patrick “only has boys.”

“Bad”: when a sex cult can afford Roofies but can’t shell out for some lube.

Escaping from a cult is a fascinating premise, but uselessly unexecuted if the audience remains even more in the dark than the victim and her family at the end. A good storyteller shouldn’t spell out everything — the scene in “Psycho” where we never actually see the knife touching skin — and can leave loose ends — what happens at the end of “The Sopranos,” or “Inception”? But what could have been the best parts of “Martha Marcy May Marlene” are the ones Sean Durkin never wrote, never even imagined maybe. This does not come off as smart subtlety, but rather the irritating reverie of someone who’d rather let his hand-held camera drift on a young woman’s disturbed, beautiful face, letting her eyes tell more of the story than perhaps he is capable of doing.

Run as fast as you can in any direction if you ever hear anyone utter this phrase, part II.

Maybe what people like about this movie is imagining those missing scenes: what Martha was like before the cult, how she heard about it, what the pitch was, what broken or premature part of her was intrigued by the idea. If the writer himself doesn’t thrill to the idea of even hinting at those things, and we applaud his decision, we’re as trusting as any of the cult members, willing to accept that we don’t need that information.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in the theater anymore. She lives in North Hollywood, near the In-N-Out Burger.