Melancholia

Watching “Melancholia“‘s depiction of two deeply troubled sisters, reckless Justine and severe Claire, facing the actual end of the world at the former’s wedding reception and soon after, one might fixate on the tragedy of it all — the children who won’t grow up, the pitiful confusion of dying birds and horses, the ivory-skinned nude moon-bathers about to be crushed into oblivion, the utter inability to do anything.

Or, even worse, one could revert to English class mode and see a film like writer/director Lars von Trier’s masterful latest work as symbolism, with Melancholia, the made-up planet destined to collide into Earth that gives his latest film its title, just astrological shorthand for the human experience when pulverized by gloom.

To do so would be a mistake, but it appears to be a mistake many have made, upset at the darkness of it all, as though actions taken when one is convinced the world is going to end aren’t necessarily going to be a little dreamy, a little crazy, a little indulgent. As though the pageantry of a silly, six-figure wedding has more significance than two planets smashing into each other at 60,000 miles per hour, to the sweeping majesty of Richard Wagner’s throbbingly fatalistic score to Tristan Und Isolde, repurposed.

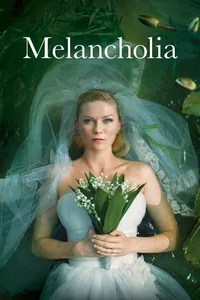

And in the same way Wagner said he wanted to highlight that opera’s “all-pervading tragedy,” von Trier gives this movie’s power to Dunst, who reboots Shakespeare’s character Ophelia, from the most famous Dutch tragedy of them all. In von Trier’s movie, which even begins with an extreme slow motion montage that features a stunning image of Dunst floating down a lily-filled river at night, his Ophelia responds to a weak husband unable to take power and a stiff-with-fear sister and brother-in-law by rising above and beyond them. At one point Dunst’s Justine tells her sister, “If you think I’m afraid of a planet, then you’re too stupid.”

Justine’s actions horrify, not because they are wrong but because, convinced that all life is ending — and for our purposes, it might as well be — she is reacting with honesty instead of sensitivity to social norms, extending the cool middle finger usually reserved for a Philip Marlowe or a Meursault or a number of other male characters, asking for a cigarette on the firing line instead of blubbering hopelessly.

This isn’t just a story about a bride who, in the final days of the earth, can’t help but be unimpressed by the reception’s location, her brother-in-law’s mansion, its 18-holes of golf and stable, nor the Bridezilla drama wrought by the haughty, humorless guests at her wedding reception, where Justine’s mother, covering damage with unpleasantness, gives the party a speech about how she doesn’t believe in marriage, while Justine’s boss publicly pesters her to turn in a tagline for an ad campaign and Justine’s new husband announces they’re going to spend the rest of their life on an orchard just because he had an especially tasty Empire apple when he was a kid.

To borrow a Wagner phrase, Justine’s reactions, even when crippled by a wave of sadness, are “ecstatic expression.” It’s the uncaring naughtiness of ripping a rich, expensive hunk of a wedding dress when it gets snagged on a solitary midnight jaunt. It’s the pent up delight of telling one’s boss that his company is morally bankrupt. It’s the delight of taking an unladylike swig of Hennessy from the bottle on the dance floor because dealing with your unhappy new husband in any other way wouldn’t even be worth it.

Facing the end of the world, Claire is horrified. She tries to flee into town, and when the only working vehicle she can find, a golf cart, runs out of battery power, there’s a pitiful picture of her, bedraggled and gray, trying to carry her son across the golf course, dodging appropriately sized hail in some exhausted upper class version of combat.

Justine, on the other hand, is completely uninterested in playing along with the rest of the world as they experience the disaster. Still in her gown, she pees on the golf course, looking up at the stars, and a little bit later, grabs one of her guests and mounts him in a sand trap, because desecration doesn’t matter. She tells her boss his product is evil and lousy, and ducks out of her wedding reception to take a bath, because insult doesn’t matter. And when death appears imminent, she fully redeems herself with a sweet and selfless act, because she understands that even if we on this world are alone, being prepared for death — that matters.

Ashley O’Dell writes about movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.