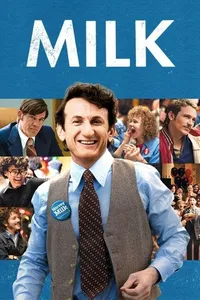

Milk

So why do we need a movie about Harvey Milk, a Korean War Navy vet who left an unremarkable life selling insurance in New York at 40 to become an openly gay San Francisco politician, assassinated in 1978? Since we’re asking, we ought to consider that there are movies in the works right now based on Candy Land, Battleship and a re-make of Clue (about as smart as re-making “Psycho” — you’re forgiven now, Mr. VanSant).

If nothing else, “Milk,” is some kind of triumph to be shot all in eight weeks, on location in San Francisco, on a budget of $15 million. You can’t even rent a studio apartment for that long in the Castro for that little money. It helps that “Milk” had an Oscar-winning predecessor, 1984’s “The Times of Harvey Milk.” Both begin the same way — faded RGB television footage of Dianne Feinstein on autopilot, announcing to a media circus that the city’s mayor and supervisor Milk had been shot … and that they’d been shot by Dan White, another supervisor who’d tried to resign a few days earlier.

But this “Milk” brings to life the most important element — the man himself.

This movie could have been too precious by half. Sean Penn playing a gay martyr — one who used the word “hope” a lot — in a movie that was released two weeks before the general elections in California, in which a certain crowd hoped the forces would rally to elect the nation’s first black president and soundly trounce California’s gay-marriage ban.

Instead, Penn is mesmerizing, rallying Teamsters to support him by getting the gay bars to boycott anti-labor Coors. A threat letter written in blood-red crayon goes on his fridge, to be giggled at triumphantly. But Penn’s eyes also crinkle with the crow’s feet of a man in his late 40s, a man charged with a cause (with Emile Hirsch, who played the lead in “Into the Wild,” in another fluidly perfect role, especially recalling a Spanish drag queen’s scalping by police rubber bullet) and buoyed by love (with James Franco, eschewing the usual Seth Rogen stoner fare and keeping his head above bongwater).

Even his killer, Josh Brolin, as Dan White, brings both the sober face of his politician and the uncertain twinkle of fear and desperation in his eyes, the kind of spark that leads a man to blame a killing spree on Twinkies (that’s the Twinkie Defense, Gen X-ers. Your parents didn’t make it up).

It’s just too sad that the picket line stock footage still looks like it could be nightly news — with more muffin tops and in color. There are still plenty of Anita Bryants out there, the citrus queen who called homosexuals “human garbage” and blamed the drought on them (and maybe global warming on the AIDS quilt, too, as then-funny Dennis Miller once said of the far right). As generations pass, the baby blankets of “Matzoh is really dirty jokes in braille!” “The Cubans plant pro-Castro messages in their guajiras!” and “The Irish drank all the whisky!” (blame them for the drought?) get more and more tattered and eventually dissolve like a back pocket full of receipts through the wash.

Milk “knew that the root cause of the gay predicament was invisibility,” according to a writer for Time. In addressing that invisibility, Milk once said, “The first step is always hostility, and after that you can sit down and talk about it.” We’re still at that hostility step, a lot of us. Tattered blankets can hold for a long time. But that means that there’s an after. At least, there is, yes, hope.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.