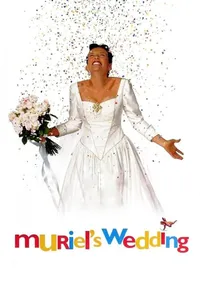

Muriel's Wedding

Now this is how you make a movie about a woman who wants to get married. A main character who is down on her luck but who’s lovable enough and has the inner strength to overcome her situation. Human interactions that don’t rely on unreal tension-building cliches like “woman cruelly rejects man’s goofy attempt at romance” and “woman overreacts to minor misunderstanding by derailing the plot.” And humor that doesn’t rely on gratuitous diarrhea jokes and cat fights.

“Muriel’s Wedding” at first appears to be the story of shallow, wide-eyed Australian Muriel Heslop (played by Toni Collette) who’s not quite fragile, demure or tiny to be the bride she dreams of being. She’s a confidently tacky vision in three patterns of leopard spots (including a leopard scrunchie) at a neon pink taffeta wedding, and when she catches the all-important bouquet, her friends turn into the screeching jungle animals because obviously Muriel is not getting married anytime soon, amirite?

Her exit is even more inglorious: in a police car, accused of having shoplifted the leopard-print monstrosity.

Finally at the family home that houses her, her fellow grown-up slacker siblings, her checked-out mother and her failed politician father, she retreats to a childlike fantasy of magazine cutouts of beautiful, serene goddesses in imported silk chantelle and a soundtrack of Abba songs.

“Useless,” Dad, a former local politician, who’s sent the cops away with a case of beer, tells his brood, including one sister who wears one of his old campaign shirts every day. “You’re all useless.”

The uselessness of her family established, Muriel attempts to bond with her fellow gal pals at a glorious dive called Breakers, a turquoise reef-themed bar serving luminous, tackily named drinks in shapely glasses with umbrellas. They have bad news — she’s not cool enough to be their friend, and especially not cool enough to go with them to a local party island — but don’t want to break it to her harshly.

“Let her finish her Orgasm first!” one of the shallow bints says.

But then Muriel gets a break. A family friend offers her an entry-level Avon-type job selling makeup on commission. To buy her first kits, her mother gives her … a blank check.

“I’m going to get married and be a success … I’m going to show them all,” Muriel tells her mother, before taking the check and rocketing herself into a fabulous vacation on the very party island her ex-friends are donning coconut bras for tacky resort talent shows. There, she re-connects with another social outcast from high school, Rhonda (Rachel Griffiths). They don wigs and horrible white satin costumes and dance poorly and, somehow, sing a transcendently joyous and biting version of “Waterloo,” directed squarely at the miserable snobs who snubbed them. They decide to leave their backwater town of Porpoise Spit for Sydney, to get jobs and enjoy time with men — one double date that ends with Muriel furiously yanking what she thinks is the zipper on her leather pants ends with raucous laughter, styrofoam confetti raining down into her cleavage, as she accidentally empties the zippered beanbag chair on which she was having her petting session.

When she finally gets her wedding, there’s absurdity, but no hate. There’s regret, but no contempt. There are compromises, but they are not soulless sell-outs. Every guest in the crowd looks aghast, even the groom, but Muriel beams — she’s happy no matter what the silly circumstances are she had to get through to get hitched.

What seems to be a betrayal — an out-of-nowhere courtship that leaves a suddenly cancer-striken Rhonda (“Oh God, I’m going to have to go bald and eat macrobiotic food!”) vulnerable — is one of those uncomfortable, rapid-fire adult circumstances that leaves those who handle it well so much better off than those who crumble like a stale Tim Tam. You’d be as wrong to dismiss or disdain the seemingly one-dimensional as Muriel’s so-called friends were to dismiss her for not wearing “the right clothes.”

In the beginning, Muriel believed that “If I can get married, it means I’m a new person!” Over the course of the movie, wedding or no wedding, she discovers that she can achieve that transformation (“I’ve always wanted to win,” she says) on her own. In Sydney, she tells Rhonda, “my life is as good as an Abba song. It’s as good as ‘Dancing Queen.’” Ironically, the woman she transforms into at the end of the movie would likely have no lack of proposals, but she might just feel OK without them.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.