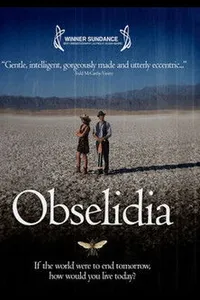

Obselidia

Calling a movie “immature” usually calls to mind the diarrhea-in-a-sink scene from “Bridesmaids,” Ace Ventura emerging from the rear end of a Rhino or the horny teenage boy thrusting into an apple pie scene from the now series that will not die, “American Pie.”

But deep thinkers can be immature too. “Obselidia” is filled with them, and filled with the ponderings of high school literary magazine types with a few toil-less decades on them. Our fragile hero, George, armed with a typewriter, some stamps, a crummy old video camera and a job at a library, is compiling an “encyclopedia of obsolete things.” This idea would be tolerable coming from a 15-year-old with badly dyed hair and a lifetime of growing up to do, but when it comes from a middle-aged man who smirk-cringes when an attractive library patron thinks his knowledge about 17th century writer Thomas Browne is intriguing — then turns down her dinner invitation — it’s heavily irritating.

Set to forcedly dreamy toy piano and accordion music, George has already told the audience he believes the world is in decline, and that he’s the last encyclopedia salesman in the world. His “encyclopedia” is actually a project in which he interviews people like an older man who used to go to movies a lot as a kid, then watches the videos and types on an old typewriter “the magic is gone.” He has a beer with a neighbor (George drinks his from a glass) and shoots down the guy’s cheerful observations about the heavens by saying he doesn’t like shooting stars and that love is “obsolete.” This guy doesn’t sound like an adult with a job; he sounds like a 14-year-old with no bills to pay who’s just discovered black eyeliner and My Morning Jacket.

As the movie has obviously set him up to do now, he finds love. Sort of. Slogging through his bogus encyclopedia project, he interviews Sophie, a lovely projectionist who also tries to flirt her way into his life. Her interview, by the way, he turns into the following magnetic poetry: “It will all be gone,” a life condensation I’d imagine would be highly irritating for any working person who’d given up an afternoon to be recorded on tape for an encyclopedia. But that doesn’t occur to George, who we see frequently pedaling his old timey bike in slow motion, a near sneer on his face, dressed in R. Crumb-lite garb, offended by the garish modernity of a spandex-clad cyclist even though George was riding in the middle of the street.

The lovely Sophie — who wins George over by finding his place via phone book, which is just so old-fashioned and quirky — is too much of a good sport, though, and indulges George by offering to drive him to Death Valley to meet an even more unplugged author who thinks humankind will be destroyed by climate change in the coming decades.

First-time writer and director Diane Bell really has created a relatable, darling character in Sophie, who asks George why he hasn’t interviewed any fishermen for his project, and gently enables his navel-gazing specialness by calling it “now-stalgia.” Like a champ, Sophie puts up with his superficial disdain for America (a country “set in stucco,” he says) and bad Philosophy 101 pick-up lines — “The notion of perfection is a platonic trick to make you feel inadequate … I don’t think honesty’s the most valuable trait in our society” — with a smile.

Sophie speaks for the audience, gently imploring George to tell it to someone whose every movement in life isn’t calculated to be virtuous, people who use computers and cars not because they’re shallow but because they have things to do and people to take care of and have no energy leftover to be self-satisfiedly outre, cloaked in slow motion and new age soundscapes and nodding agreement of other misanthropes. The idea of humanity’s imminent demise “doesn’t upset me,” Sophie responds, in what could just as well be an indictment of the movie as a whole. “It just bores me.”

But George really isn’t listening. To him, humanity might as well have already died out. He appears queasy at the mention of distasteful modern culture, squirms while scientifically trying to excise himself from 21st century America. He’s an off-the-grid polisher of his own superiority, the star of a one-man perfume commercial for Eau De Better-Than-Everyone, with all the angst and none of the rock of Weezer frontman Rivers Cuomo in 1994. If “Obselidia” is a love story, it’s the tale of George being in love with George.

Ashley O’Dell writes about movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.