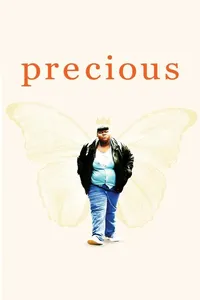

Precious

“Precious” grew on me. In the days after watching it (which, itself, was an experience that frequently felt like many of the warning signs for a heart attack) I felt fond, protective toward not just the main character, but the assorted supporting characters — a teacher, a counselor, a nurse, her classmates.

The story, about a morbidly obese 16-year-old black girl whose sexual abuse — at the hands of both her mother and father — has left her with a 4-year old daughter with Down syndrome, another baby on the way, and a killer survival instinct. She uses it to imagine herself on the red carpet, a magnanimous superstar in velvet and feathers and leopard prints, as her father rapes her, or neighborhood thugs tackle her onto the sidewalk. This girl could sleep on nails, eat broken glass and walk on hot coals without flinching. It’s nothing compared to what she gets every day at home, a stage set deftly in front of us as the television spins endless fantasy in the background (in the midst of the grim filth, the ladies of “227” blab contrivedly about a teen beauty pageant before “$10,000 Pyramid” contestants finish each other’s sentences meaningfully: “And this is when you make a fast…?” the first one hints. “Escape!” the second guesses).

“The other day I cried. I felt stupid,” Precious mutters in voice-over. “But fuck that day. That’s why God or whoever makes other days.”

Then, her overcrowded zoo of a school recommends her for an alternative high school. Her pre-GED class is a tiny classroom, one teacher (Paula Patton, a kind, educated lady the type Precious has never encountered, who talks “like TV channels I don’t watch,” she thinks to herself) and a handful of what they like to call “at risk” girls. At risk of what? It would be easier to say what they’re not at risk of. Lessons are simple. Learn the alphabet. Sound out words. Read. Write in your journal. She sorts things out there and they come out easier when she has her meetings with her social worker, like that her father “gave” her the baby she’s got “and the one before.”

This isn’t even as bad as it gets in the real world. They had to soften some things to make a movie out of this kind of story. It’s not good business to have audiences throwing up in their popcorn.

This is “The Wizard of Oz” in hell. Horrible things lurk around every corner. When Precious trudges up the stairs, home, with her newborn, she looks meaningfully over the landing, as though her baby boy might suddenly topple over. In fact, what happens when she gets home is far more terrible. A shot, soon after, of a church in front of a building with a full side painted with a plea to spay and neuter one’s pets, makes your stomach churn with the question raised.

I haven’t seen such phenomenal, subtle, dead-on acting by an entire cast of a movie in a long time. Gabourey Sidibe, as Precious, is heartbreakingly wonderful, seemingly dead on the outside but dreaming of joy on the inside in startlingly different dream sequences.

Genuine, non-syrupy compassion for characters like this is almost unseen outside of John Waters films. Mo’Nique, as her mother, has turned her own wounds into chilling hideousness. She is the kind of villain who makes 3D superfluous. When she lunges across the room, smashes a pan against the wall, hurls a television, you duck. As for Mariah Carey, who plays the social worker, she was unrecognizable and amazing and for the first time in my life, I can acknowledge her talent without reservation.

A wretched ton of viewers and critics, squirming with discomfort and disgust through the page, think the story is exaggerated. It’s anything but. This is the absolutely quotidian detail of humanity’s inhumanity. One British critic wrote, “What exactly is the point of committing all this horror to paper?” This isn’t madness, it’s blindness. Precious’ life is is no rising tide of horror, degradation, violence and abuse. It is a wave, endlessly slapping, crashing and crashing, and as urgent as a rip tide. As a movie, Precious’ story is uncommon. As truth, it is anything but.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.