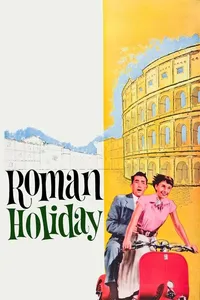

Roman Holiday

I couldn’t make it through the 1961 classic “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” so insufferably shallow and ditsy was the twiggy, privileged flirt, window-shopping through life, an icon of absolutely ordinary passing as quirky. So had I known Audrey Hepburn was the star of “Roman Holiday,” I never would have put it on my Netflix queue — especially since it’s a movie about her being a princess. Gag me with a long black cigarette holder.

But amazingly, “Roman Holiday” turned out to be about the best princess movie I’ve ever seen.

It may be almost 60 years ago, but her Princess Ann is living much the same life as one imagines the new Princess Kate (yes, yes, she’s a Duchess) is living. She tours Europe, affecting a fragile porcelain gaze, waving a silly, limp wave from a pumpkin-like carriage as organized marchers and dancers from all the nations perform and parade before her, like a C-SPAN version of “It’s a Small World.” In an endless, multi-lingual greeting line, the camera goes beneath her skirt as she takes one foot out of her uncomfortable pumps to stretch, then another.

One evening in Rome, it’s all too much.

“I hate this nightgown. I hate all my nightgowns. And I hate all my underwear too,” moans Ann in her high-necked, floor-length sack of a nightdress, flopping on a big bed, her night in the hip yet ancient capital ended irritatingly early, with dancers still celebrating outside. “I’m not two hundred years old! Why can’t I sleep in pajamas?”

The countess who’s minding her at the palatial embassy is aghast: “Pajamas?!”

Ann counters: “Just the top half.”

Whoever this princess is, she’s tremendous — more so after her hysterics prompt the embassy doctor to inject her with sedatives. Instead of being knocked out, Ann has an “Office Space”-like epiphany and, emboldened, gets dressed and jumps out the window, escaping the embassy grounds in the back of a three-wheeled delivery truck, tumbling out onto Rome’s streets like a time traveler.

It’s there that journalist Joe Bradley (played by Gregory Peck) finds her, snoozing on a low brick wall. A gentleman, Bradley takes her to his one-room apartment, where she woozily recites Romantic poetry and insists it’s Keats (it’s Shelley, and Bradley knows this: he calls her a “screwball” and flops her good-naturedly onto his couch so she can sleep it off).

One imagines the deeply in debt Bradley sells out the flopsome princess for a well paying scoop and the princess, confronted with the real world, flings herself into the arms of the tall, dark stranger. What actually happens, though, is that she emerges the next day, ditches her high heels, gets her hair chopped off, buys a gelato, takes a moped for a joyride, and engages in such a wonderfully choreographed game of deception with Bradley (she says she’s run away from school, while he says he sells fertilizer) that it couldn’t possibly end properly without her smashing a royal investigator in the head with a guitar and jumping into the Tiber River with Bradley to escape.

Hepburn won an Oscar for her performance, and succeeded in portraying just about the only movie princess to whom I’d introduce a young girl. This princess is fiery and capable, neither willing to give up adventure for rote selflessness nor to give up her inherent duty for fleeting fun.

Princess, in movie parlance (see the atrocious “Princess Diaries” and almost every Disney toy ad, er, movie ever made) is too-often shorthand for what plastic-mongers believe should be the sparkly pink dreams of pretty girls. A princess is a wide-eyed virgin waiting for a man to take care of her. A princess is a girl with luscious Barbie hair whose virtue is rewarded in impractical dresses and ridiculous jewels. She is a female archetype that dull-witted writers can understand because she is empty and there is nothing to understand, nothing at all except that she depends on you and wants you, in a tepid, buttermilk way.

“Roman Holiday” knows nothing of that mold; were it released today, it would rightfully make the rest of the “princess” genre look like what it is — in the delicate terms of Joe Bradley, “fertilizer.”

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.