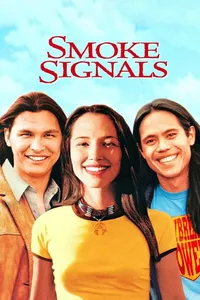

Smoke Signals

One day in college, I asked about a fellow student’s “Frybread Power” T-shirt and he told me about “Smoke Signals.” But it took eight years before I could find a copy of the movie to rent.

Writer Sherman Alexie has said he hates earnesty, but also that he was soaked in booze when he wrote the story “Smoke Signals” was based on, and embracing sobriety when the movie was made. That explains a lot, like how almost immediately, the movie can’t decide if it’s sweet or in pain.

Lester Fallsapart, parked at a dirt crossroads in a stunning, stark landscape, gives a traffic report to the local radio station on the Couer d’Alene reservation in Idaho. It’s the Fourth of July. There’s a party. Suddenly, a house goes up in flames. A Tony Soprano hulk of a father, played by Gary Farmer (“Nobody,” possibly the only man who could be the bigger badass next to Johnny Depp in Jim Jarmusch’s “Dead Man”) saves two infant boys from the fire — his son and another boy, whose parents die in the fire.

As the boys grow, Farmer’s character lets his seeming act of heroism destroy him, sawing off his cape of hair, drowning his sorrows like a modern-day Ira Hayes. He smacks his kid, his wife, and takes off for good rather than give up his beer. Years later, the boys are young adults when they get the word he’s died and have to pool their resources to go to Phoenix to retrieve his ashes.

Alexie and first-time director Chris Eyre aren’t going anywhere new with that plot arc, but there are enough sweet parts in the movie to keep it from feeling entirely like rez-sploitation, like the two girls who’ve resigned themselves to drive a beater stuck in reverse, presumably until the transmission gives that gear up too. Or when one boy remarks to the other that one rarely saw John Wayne’s teeth in movies, they strike up an impromptu song, in heavy, rhythmic, keening, pow-wow style, about said chompers. After meeting a girl who claims to have almost made it as a gymnast, they turn her improbable claim into a joke after she’s gone. “Hey Victor, did you know I was an alternate on the 1980 Olympic team?”

The movie had to act as a production proud it was made by, and starred, American Indians. But it also had to act as bridge to white cinema, and the attempt to make it there created some awkward set pieces.

One says to another, “You know the way Indians feel about signing papers.” Another says, “We’re Indians, remember? We barter.” That’s straight off the rack. The exiled father tells a tall tale about his son sinking a hoop “like an angel with TV-dinner tray wings.” That not striking Alexie as “earnest” is about as tone-deaf as turning the Trail of Tears into a sequel to “Oregon Trail.”

Finally, there’s the fry bread. If someone’s mom isn’t kneading it and dropping it tenderly in the oil to fluff, someone else is bragging about his favorite recipe, and someone else is wearing a “Frybread Power” shirt and finally, someone’s telling a story — with slo-mo flashback — about the time a lady made 50 pieces of fry bread serve 100. Get this, she raises one above her head and triumphantly tears it in two! Did you just have your mind blown?

That one expects more from the niche of American Indian cinema is a good thing. It’s too bad I didn’t take the advice of my classmate and find the movie somewhere years ago. Though I doubt it would hold up, the teenage me would have liked it even more.