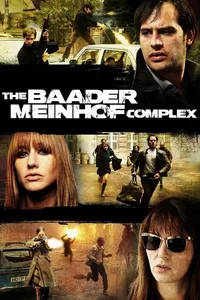

The Baader Meinhof Complex

Any peace-loving, rational adult watching “The Baader Meinhof Complex” will likely feel an ever-increasing level of disgust with the main characters and a growing wish the filmmakers would spend a little more time with just about the only sympathetic character in “Complex.” That’s 70’s German Police Director Horst Herold (played by Bruno Ganz, the star of the YouTube parody meme in which his Hitler complains about Leno moving back to late-night, kvetches that Lady Gaga is screening his calls and rants about the vuvuzela).

It feels backward not to root for the sexy, chain-smoking, fashionable, gun-toting rebels in black sunglasses and to, instead, think, “Gosh, German government. That sure is a great plan to test nascent data-processing technology to pinpoint the gang’s crash-pad in Berlin. You fight the good fight, Federal Criminal Police Office!” But the Baader Meinhof Complex (which would be more accurately titled “Gang” instead of “Complex,” which confusingly makes the subject of the film sound like something in the DSM-V, instead of a small, Germanterrorist network) spends little time dwelling on the causes of youth discontent and violence and how a society can foment a culture of non-violent protest and constructive disobedience. Instead, we watch opinion columnist Ulrike Meinhof peer-pressured into trading her widely read rhetoric for robbing banks in the name of Che Guevara. Arsonist gamine Gudrun Ensslin, crashing with her boyfriend Andreas Baader at Meinhof’s family’s home, confidently explains her threadbare rebellion: “We’re forming a group. We’re going to change the politicalsituation.”

“How is that possible?” Meinhof says.

Baader explodes, childlike, at her: “What a f***ing bourgeois question! We’ll just do it, or we’ll die trying.”

The pen, in this movie, withers like a daisy in the face of guns, guerilla-training camps, Molotov cocktails and pram-concealed automatic weapons. To what end? The ecological misfits in Ed Abbey’s “The Monkey Wrench Gang” burn billboards because they ugly up the landscape. They disable Caterpillars to halt development and building - or at least postpone it. They plan to bomb the Glen Canyon Dam, which flooded a museum in sandstone and has ruined the Colorado River. The exploded buildings and rapes in “Fight Club” and “A ClockworkOrange” are stylized fiction.

But the ruin, the death, the children abandoned when their parents decided to turn nihilist in Baader-Meinhof are all real.

Journalist Stefan Aust explains in the making-of that yes, we’re supposed to look at the Baader-Meinhof members - whose prison quarters, by the way, include record players, typewriters, civilian wardrobes, an endless supply of cigarettes, TVs, transistor radios, well stocked bookcases, a book-filled common room and a gated outdoor area for pacing - as “blatantly immoral,” and having “an inflated moralistic sense of the mission.” Yes, it goes without saying that bomb-throwers who would rather shoot “pigs” and sabotage their trials by calling the judges “fascists” are pompous thugs.

Why, then, linger on them looking so terribly cool as they whine and stomp and posture about their “liberation” movement? It comes off less as meticulous documentation of a group at the heart of a disturbed decade and more like a vile sympathy.

The audience loves a good criminal cadre, a satisfying uprising - the barricade-building, impoverished French peasants of Victor Hugo’s “Les Miserables,” ferinstance. Unfortunately, the only thing the Baader-Meinhof hooligans share with that work is that they, too, embody what it is to be miserable.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in the theater anymore.