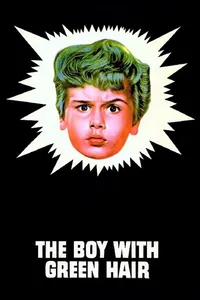

The Boy With Green Hair

My cousin Max woke up with green hair once. It was on purpose though. He was 13 and globbed bright, awesome “Green Envy”-colored Manic Panic on his blonde locks one Saturday at a friend’s house. Before my aunt found him out, he walked around downtown and was a girl magnet.

“I got to be king for four hours,” he said.

Of course, once Tia Maria marched him off to the family barber, it was all over. When the peroxide didn’t do it, they tried acetone. And when that wouldn’t do it, Max ended up a baldie.But if it was that shocking in a good sized city in the mid-90s, imagine how shocking it would be in 1948, when “The Boy with Green Hair” shocked the nation. (Chlorine wasn’t cleared to be used in pools until 1948, the year the movie came out, so even blondies wouldn’t have been familiar with the now-tradition of green streaked summer locks.)Boy star Peter Fry (Dean Stockwell) is aghast by it. He’s a serious little orphan who’s gone from home to home until finding respite with an old man he calls “Gramp” (Pat O’Brien), a former actor who tells him he can go into any room in the house and touch whatever he likes (can you imagine your own grandparents saying such a thing?) Gramp doesn’t blink when the new arrival to his home picks up a vase and smashes it, perhaps testing the man’s good temper.

“I’ve been meaning to get that out of people’s way,” Gramp notes.

“I did it on purpose,” Peter admits quietly.

“I know what you mean,” the man says.

Peter agrees to stay. Gramp tucks him in and turns out the light, heading out to night work as a singing waiter, and calms his new, lonely, troubled ward with a simple, “There’s nothing there in the dark that wasn’t there when the light was on.” Your heart hurts at how loving these interactions are.Of course, things soon fall apart, as they do in second acts. At school, Peter discovers he’s a war orphan. As much of the world was thinking at the time of the movie’s release, just a few years after atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Peter worries the whole world will be blown up, leaving behind nothing but him and others like him, sad souvenirs of a world that couldn’t keep itself alive. He is a walking propaganda poster to other children, a reminder to give charity and buy bonds.

And this realization manifests itself when he gets out of the bath one day with green hair. He is immune to the neighborhood girls who call it “super,” Gramp, who tells him he once had to patch the seat of his trousers and was noticed by no one. His teacher, Miss Brand (Barbara Hale, pre- her role as Perry Mason’s secretary) is a stony, film noir superhero: noticing Peter’s being teased, she tallies up how many of the class have black, brown and blond hair. How about green? One. And how about redheads? Also one. The meanies shut their faces.Retreating, as boys do, on bikes to forests, Peter imagines the other war orphans in the posters and vows to use his shocking green hair as a symbol of how war is bad for children and how there shouldn’t be another one. This sounds facile. It’s not. If you were his age, you were probably hiding under your desk during bomb drills. He wasphilosophizing.The print of “The Boy with Green Hair” that’s on Netflix has a sometimes muddy sound quality. The colors aren’t crisp. Telling a story in flashback and montage, as it does, is no longer innovative. And Peter’s final leap might be seen as totally naive and hopeless without the memory that, for decades after the movie was made, nuclearobliteration was a nearly daily consideration for even those haves in America who could fortify their lives against most things — but never against this. Things were utterly senseless, in a terrifying, sometimes liberating freefall. You could wake up with green hair. Or you could never wake up again. Neither one was so shocking anymore.Ashley O’Dell writes about movies that aren’t in the theater anymore.