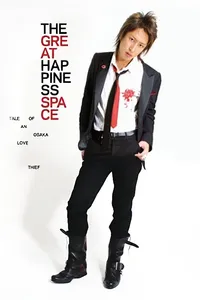

The Great Happiness Space

My father’s year working in Japan in the mid-90s introduced him — and me, by postcards and packages of mangosteen-flavored gum — to an incomprehensible world. Coffee came in cans and contestants in a TV game show plunged their hands into scalding water to snatch coins from the bottom of a tub — years before the Starbucks Doubleshot and “Fear Factor.” This was a country that named its cars “Sunny California” and its gum “Poison” and its canned water “Sweat” and sold used schoolgirl underwear from vending machines and bought used 501s for hundreds of dollars a pair. It was a strange mix of whimsy, sadism and artfully packaged ramen that came with its own spork in the package.

At first, Osaka’s Rakkyo Café in the documentary “The Great Happiness Space” seems to fit into this bizarre puzzle like a square watermelon in a compact Japanese fridge. Slouching, skinny young men outfit themselves in expensive watches and trendy suits, iron their emo hair and … prostitute themselves for exorbitant hourly rates, inflated by ridiculously overpriced champagne.

Unlike their female “drinkie girl” counterparts, the men, or “hosts,” are mostly in control of the “fake love relationship’s” give and take. They flatter like adorers, then scold like concerned brothers, try to avoid sex — because the relationship will end — and mostly down glasses of cloudy nigori and clutter the tables with Asahi cans. The girls spend thousands of dollars a night mooning after the hosts — especially Issei, the club’s 22-year-old owner.

It’s tiring work, he says: “I have to compliment girls all the time.” For that toil, he earns $50,000 a month. Other hosts? About $10,000.

The practice is weird enough seen with just that information, but at 32 minutes into the 75-minute film, we learn why these seeming spoiled, rich girls are willing to throw down so much dough on these pretty, unthreatening boys. One of the girls, being interviewed in an empty stairwell about her expensive habit, talks about how she feels shunned and hated by the world. A janitor walks by, in between her and the camera man. The girl clams up as he plops down his broom and dustpan and sweeps up a landing. She looks at him, at the floor, waits until he is out of earshot to continue. It breaks your heart.

In the morning, the hosts carry each other out of the tiny fifth-floor doorway in their anonymous building, into the concrete. One rides off, painfully hungover, on a tiny bike with a little basket. And he’s the one on the winning side of the night’s transactions. Issei, who apparently agreed to the film if it would not be shown in Japan, tells the filmmakers, “It’s quite heavy.”Japan is full of things you could spend a lifetime failing to understand. This melancholy, ungainly grapple with loneliness turns out to be not one of them.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.