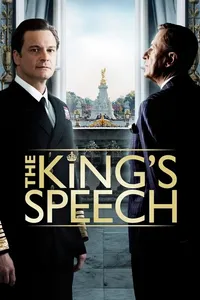

The King's Speech

I can almost guarantee that everyone reading this review knows someone who is going through something far more debilitating, insurmountable or destructive than a monarch overcoming a stutter. And not just any monarch — England’s King George VI (or “Bertie,” played to frustrated perfection by Colin Firth) in the last, pre-World War II days when that little island controlled 58 countries, almost a quarter of the world’s population spread from Bermuda to Brunei. (The U.S.’s power looks positively indie in comparison.) So why bother watching?

As a period piece and history lesson, “The King’s Speech” (rated R only for a long string of shouted, naughty words, including “bugger” and “willy” the doctor compels Bertie to use to un-tie his tongue) earns high marks for its charming ability to plunge the audience up close into pre-war Great Britain. You can almost taste the smog, shiver at the vast, unheated rooms, feel a little faint at the caste customs and still-intricate fashions. It’s 1925 when the movie begins, and the Duke of York, the son of the current king, is asked to give the closing speech at the Empire Exhibition. His nasal, halting voice is a ticking shrapnel, wounding his people in the crowd, and even trembles a little when he later gives his two young daughters (one, Elizabeth, the current Queen) a story about the trials of a reluctant penguin — himself, of course.

Now, it’s important to note that this king is no pillow-carried monarch, and, in the movie at least, saw the monarchy as “indentured servitude.” (This is something we rebel against in this country because our celebrities have mostly chosen their terrible fates — even child stars like Drew Barrymore and Michael Jackson get little sympathy once they are of age to run screaming into happy oblivion.) But the king was a naval officer who distinguished himself in World War I by doing actual, life-risking work. He didn’t want to be an actor. He didn’t choose this firm. He could have been born — knock-kneed and left-handed, which in those days was forced out of children — into any normal, working-class family, and his ability to give a speech wouldn’t have been important at all.

After rushing through the abdication of the throne by his older brother Edward, who quite uncomprehendingly must marry the snapping charms and cold, ancient face of twice-divorced American Wallis Simpson, the most fun the movie has is in showing how Australian non-doctor Lionel Logue (the confident, ambitious Geoffrey Rush) nearly cures him of his disability. He claps headphones on him so Bertie can’t hear his own voice. He snatches cigarettes — a doctor’s prescription — from the royal paws. He rolls the king to and fro across the carpet. He encourages him to sing his words, teaches him how to sway, to pause, to distract himself and to open up, so that he admits that when he was young, he was silenced, and starved by his nanny. When Bertie’s wife, played by a demure but strong Helena Bonham Carter in a nicely non-psychotic role, wells up with tears, so do we.

The major success of “The King’s Speech” is that one feels a comparable amount of sympathy for a king as they would for a commoner. Either one with the same impediment would feel the same shame at not feeling the right to be, as he screams finally, “bloody well heard!” You might say that being surrounded by royal trappings eases some of that pain. Anyone who’s ground their way through an affliction like Bertie’s — grief, anxiety, depression — knows that’s not true. Jewels, servants, castles, retreats, can’t blast out the dark, poisonous roots of trauma. Inside one’s head, an anguished urchin and an anguished king are trapped just the same.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.