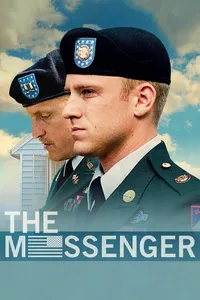

The Messenger

Busted eye, messed up leg or no, Army Sergeant Will Montgomery is not a likable person when we meet him at the beginning of “The Messenger.” Just back from combat, Will (Ben Foster) has three months left in his enlistment period — and two months into the movie, he’s engaging in loveless, passionate, linger-too-long sex with an ex who is engaged to some soft, shaggy civilian named Alan.

This is the low point of the movie, which quickly signs the steely, Eminem-like Will up with Captain Tony Stone (Woody Harrelson), a veteran of the early 90s conflicts, who has traded in booze for one-night stands fueled by hot water poured over ice. Their job? Casualty notifications. Park half a block from the next-of-kin’s house, walk up, get the name right, stick to the script, don’t hug and don’t use euphamism (“Never say stuff like lost or expired or passed away, things people misunderstand. I knew this guy who once told this old lady that her grandson was no longer with us. She thought he had defected to the enemy, started calling him a traitor. We need to be clear, need to say killed or died. What we don‘t say is the deceased or the body. We call each casualty by name.”)

It’s in and out, but it’s a rough gig. The first notification, mother and pregnant fiancee, drown in a flash flood of screaming grief — after a slap in the face. The second, a father, spits on them. Another is a woman whose father didn’t know she’d eloped with a guy he calls a “greaseball.” Another father slides, sobbing, in his tacky apartment doorway, crying, “It can’t be, it must be a mistake.” Then, there are the two parents they accidentally encounter — and must deliver the news to — at a corner store, surrounded by jam and flowers. The notification that sticks, though, is young mother Olivia (the superb Samantha Morton, from “Expired,” “Minority Report” and “Morvern Callar”). She and Will, alone in different ways, don’t become what you’d expect, though. In Olivia’s words, “Anybody looking at us would say you’re a lowlife taking advantage of my grief and I’m a slut who’s not grieving,” but both end up defying those descriptions.

“The Messenger” is not a half-hearted leap for easy truths. At times, it verges on unsatisfying stasis, but its restraint ends up being much of its beauty. There are no gritty, bloody, sandy, ears-ringing flashbacks to the war. When the two veterans are confronted by three jerky rich boys, the scene cuts away before we see them bludgeon the pretty boys. Bruised, a bit drunk, shirts ripped and dirty, they proceed to Kelly’s engagement party, where, instead of being thrown out, they mostly behave themselves. Will stands up to give a toast, and cuts it short, smirks, realizes he doesn’t need to say anything, and takes his energy to the parking lot, where he and Tony hurl themselves against cars, arms wrapped around imaginary weapons, flinging imaginary grenades, bleeding imaginary blood, feeling the numb glory of imaginary wounds.

In all these cases, the audience is primed to expect the typical: Will and Tony pounding the pampered fops who never served, Will delivering a scathing, raw indictment of his ex’s romance, which flourished as he took sniper fire and watched a fellow soldier’s face blown to a “flap,” and finally, Will grabbing Olivia, the world’s judgment bedamned, and kissing her good and hard, one hand on the small of her back, one hand in her ponytail. But what we expect would be hollow and cheap. What “The Messenger” delivers, instead, might not be called satisfaction. It is something finer.

Ashley O’Dell reviews movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.