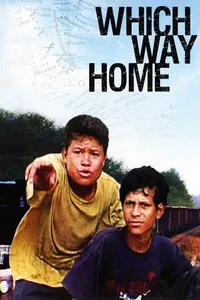

Which Way Home

A local film crew this past weekend let me hang about this last weekend on location just off N.M. 180, the two-lane highway in between Deming and Silver City, one of which contained a perhaps 200-square foot shack with a buckled wooden floor, an outhouse and bits of corrugated steel missing from its roof. Inside, the wall panels were covered with tough, poetic frontiersman-like charcoal inscriptions from Mexican men who had used the shack as perhaps their first flop over the border:: “Here were three valiant baldies the 21st of July, 1980 … don’t give up.” Another: “Don’t give up. Keep going until luck touches you.” Another: “With blistered paws and rosy bum, all alone with no one to talk to, here I am, one from Cuauhtemoc.”

Director and camera-operator Rebecca Cammisa’s documentary “Which Way Home” is an even more heartbreaking version of this story, for it tells it from the perspective of the five percent of attempted border crossers who are unaccompanied children traveling perhaps 1,500 miles alone atop train cars in hopes of making their families lives even a modicum brighter. They are 9, or 13, or 15, or 17, with a string-shouldered pack, a watch, maybe a peso or two and a baseball cap, grabbing on to the ladders of freight trains they call La Bestia (the beast) in hopes of getting to Minnesota, or Virginia, or Manhattan, all to set up a shoe shine station, or play in the snow with their sisters. Their hearts break for their mothers in Guatemala or rural Mexico or Honduras, and they must help them, they tell the camera.

We follow Kevin and Fito, young teens from Honduras, but also Olga and Freddy, 9-year-old refugees with too-hopeful smiles and too-big shoes, and families of two cousins who were found dead of exposure south of Tucson, Ariz., as they mound up bushels of orange marigolds on their regret-soaked graves after their trips went sour.

“My only treasure is my mom, but my stepfather beats her, and it makes my blood boil,” one of them somberly tells the camera. Another girl is caught beneath the train, losing her legs, and refuses to tell her family, because she doesn’t want pity; her only hope lies in taking an embroidering job.

Along their trip, Kevin and Fito will watch people be robbed by corrupt police or beheaded by train tunnels. They will see a mother and daughter trying to make the trip be raped 15 times, sleep on gazebo floors with their arms tucked inside their shirts, take charity-given fried fish with song and joy. Occasionally, they find a Christian ministry that hands out soup and crowded mattresses (the trip is “the passage of death,” one worker warns, but the U.S.A. can be “death itself” — all the migrants still raise their hands when asked if they want to attempt it), or Grupos Beta, the humanitarian group who treats their trenchfoot and gives them pamphlets about how to avoid corrupt police.

The typical response from the close-the-border crowd is that people like this should “do it the legal way,” should rely on Mexican bureaucracy as though it were as simple and ethical as waiting in line at the DMV. As though it took talent and valor to be born on this side of the border.

The men who wrote on the walls of that little shack I saw were breaking the law, 20 and 30 years ago, risking death and incarceration and loneliness to escape the corruption, murder and desperate poverty that exists just across our border, just so they could collapse in some rancher’s outbuilding and feel validated in that their names and hometowns were inscribed on a wall in America. For anyone who feels their goodness is invalidated by this, how would you feel about similar inscriptions on an underground railroad house, by escaping slaves?

I’ve never seen any documents from when my Irish and Welsh ancestors came to this country in (I’m guessing) the 19th century. I know that once they got here, they joined the military and fought on both sides of the Civil War. One ran a tugboat. One built a lumber company, and his son built houses with that midwest timber. I hope they left notes, somewhere, for fellow travelers to remember their families, as the men in the shack off highway 180 did, if they left their names knowing that might be the only record of their success in escaping before a life of honest but back-breaking labor on a ranch in Montana or a farm in Yuma, Arizona. I’d feel proud if they did. And the ancestors of the boys in “Which Way Home” — they should feel the same way.

Ashley O’Dell writes about movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.