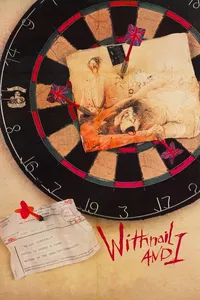

Withnail & I

For some reason, when I was a teenager in Arizona, I was out at Bookman’s, buying Procol Harum on vinyl. But when my parents raved about “Withnail & I,” which begins with a fantastic jazz version of the group’s one hit, “Whiter Shade of Pale,” I watched five minutes and dismissed it for 15 years after.

Why? Probably because an early scene has Withnail (Richard E. Grant, who cameod in “Dr. Who,” because that should narrow it down) and Marwood (the first-person narrator, played by Paul McGann) staring like shivering, cigarette-addicted city boys at a rusty-colored, live chicken they must slaughter for their dinner. Visceral, but they cast a chicken that was far too proud and smart-looking for the pot. Especially compared to the two eternal students in this 1987 British film, written and directed by Bruce Robinson, all starving artists and alcohol and speed in 1969 London, it seems.

The two are filthy, as college boys are, and idealistic and disgusted with London’s wrecking balls, runny egg-yolk sandwiches and tabloid headlines (“Love made up my mind: I –had– to be a woman”). Withnail is a bombastic actor who nearly has a death scene upon discovering “matter” in their vile kitchen sink. Marwood, drinking instant coffee out of a saucer, is a sulky writer. Their agents aren’t calling, which makes for truly a foul and pestilent congregation of vapors. But they enunciate deliciously, especially when they’ve run out of wine and have a mission: no more wine. Withnail is so dedicated to his insanity that, when he realizes it’s four hours until the pub opens one day (and he’s out of gin and cider, one of the most vile shots and chasers since Tom Robbins’ mayonnaise kick) he dons a pink rubber glove and downs lighter fluid from the can.

At first, “Withnail & I” comes off like a dark, rotating ensemble comedy, introducing characters like their violent, shaggy-haired drug dealer, with the working class accent and the Simon Cowell-tight black T-shirt and then Monty, the frustrated actor and vegetable fetishist uncle of Withnail (played by the unsentimentally piggy looking Richard Griffiths, a.k.a. the hideous, comfortable and terrified Uncle Vernon Dursley of the Harry Potter movies, except wearing a radish on his lapel). That is, until the two main characters make a rare decision: they should go to the country and sort their heads out.

Uncle Monty has just the place. Except that the city boys, who’ve arrived to “All Along the Watchtower,” have no kindling, no food and no Wellingtons. Luckily, they have the most amazing Jaguar, which only has one windshield wiper out, one headlight out, and is only half-dissolved with rust — remarkable for the marque. When they awake the next morning, the countryside is Oz-like in its vibrancy and color (even if the eel-poaching natives are a little screechy).

It’s on a frozen night that they hear the sound of breaking glass. Withnail leaps in Marwood’s bed. They whine in terror, helpless. It’s Monty. He sees them in bed. Now, a quarter century later, this would be an endlessly cheap joke. In “Withnail & I,” though, this forms the rest of the movie’s tension: how much do the friends need each other? Do they need each other like that? Why not? Why is it so hideously uncomfortable when fat, pasty Monty declares his salivating intentions to the young, bare-chested and tighty-whitied Marwood?

What good is a romantic relationship with some girl if you can’t stumble in, drunk, to a fancy tea shop where the ladies have placid pugs on their laps, and horrify the whole crowd? Marwood fights off Monty’s advances, claiming he and Withnail are lovers. This is probably the only time you’ve ever seen this, but it’s not a line meant to evoke disgust or nervous laughter. Marwood says this both in the full grasp of The Fear and the total intoxication of a ‘53 Margeaux. Maybe that’s not homosexual — maybe that’s the miracle masterpiece of troublemakers recognizing kindred spirits. No one here gets to play Hamlet, but “Withnail & I“‘s framework is a most excellent firmament, and truly fretted with fire.

Ashley O’Dell writes about movies that aren’t in theaters anymore.